A term made popular by historian Alfred W. Crosby, describing the bidirectional exchange of ideas, commodities, and species between the "Old" and "New" Worlds following [[Columbus]]'s arrival in the Americas. Among the biological exchanges were staple crops such as maize, potatoes, and cassava from America to Eurasia and Africa, resulting in the end of famine and population explosions. Domesticated animals such as horses, cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, and chickens were introduced to the Americas, where they were able to thrive. The most significant exchange, however, was the mostly inadvertent spread of bacteria and viruses from Europeans and Africans to Native Americans, who had no immunities.

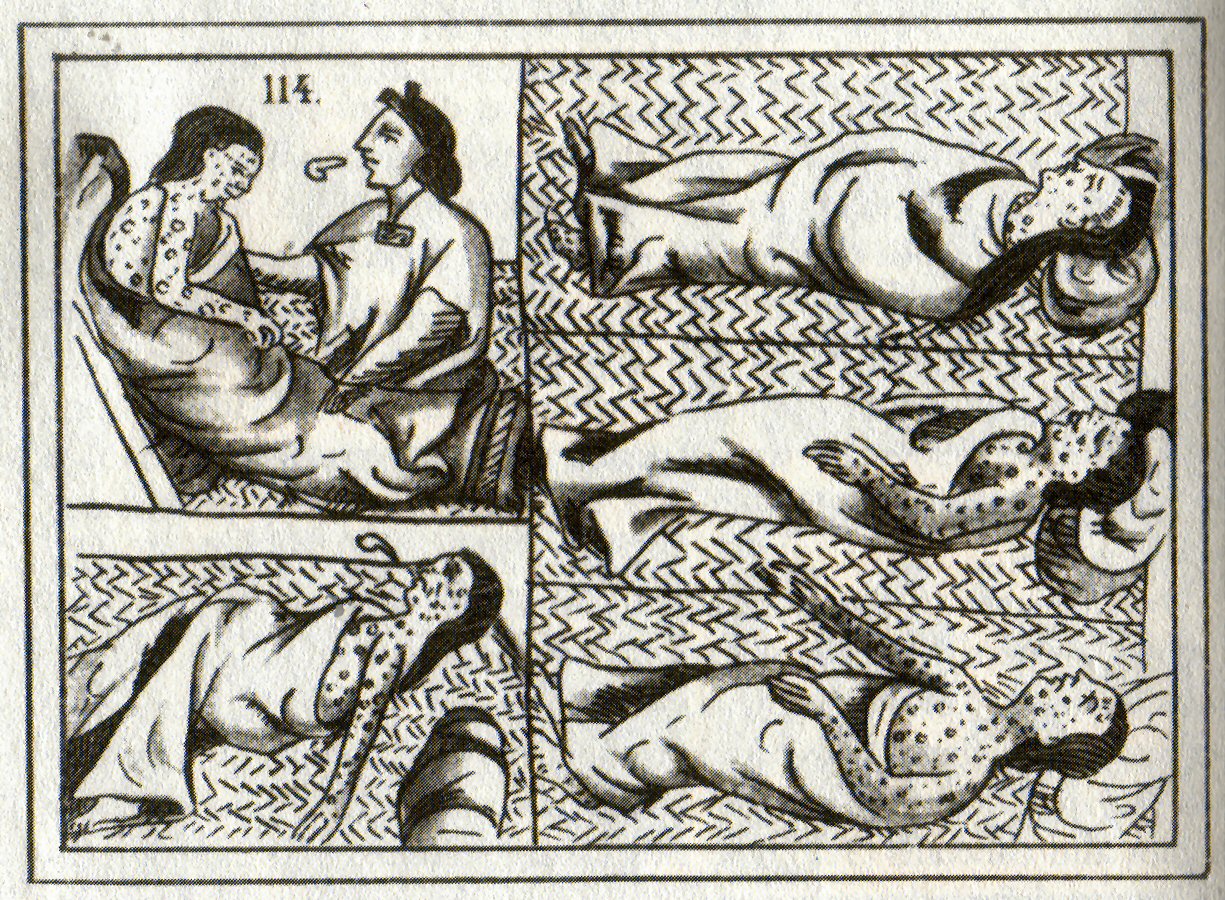

The infection of Native Americans with dozens of diseases to which they had no resistance resulted in a population disaster in which more than 90% of Native Americans were killed. This didn't happen all at once, although within a generation, populations of Caribbean islands and Central and South America were reduced from millions of people to hundreds. In remoter areas, the effects were sometimes delayed. The smallpox epidemic of 1837, for example, carried disease on river boats to remote tribes on the northern Missouri River. More than 17,000 people died, leaving only about 100 survivors of the Mandan tribe.

The social chaos produced by pandemic diseases shifted balances of power in the native world and created opportunities for Europeans they would not otherwise have had. Conquistadors like [[Dan's History Web/US 1/Topic Index/Hernán Cortés|Cortés]] and [[Dan's History Web/US 1/Topic Index/Pizarro]] took advantage of disease in their conquests and even later arrivals like [[Dan's History Web/US 1/Topic Index/John Winthrop]] and [[Dan's History Web/US 1/Topic Index/Cotton Mather]] celebrated the Divine Providence that had eliminated the natives to make room for themselves and their people.