Key Points:

• The ~={cyan}longitude and latitude system was reverse-engineered from observations of the sky,=~ particularly Polaris, rather than being based on Earth's actual shape.

• The concept of a spherical Earth was imposed on flat plane measurements through "~={cyan}correction angles=~" applied over long distances.

• The ~={cyan}curvature of the Earth is an illusion=~ created by ~={cyan}Astronomic and geodetic measurements artificially aligned=~ to make the geographic graticule conform to celestial observations.

## The Ancient Art of Cosmography

- Introduction to cosmography as the unified study of Earth and cosmos

- Early civilizations' views of the interconnectedness of heaven and Earth

- The role of celestial observations in understanding terrestrial space

In the annals of human history, few pursuits have captivated the imagination and intellect of our ancestors quite like the study of the cosmos and its relationship to our terrestrial home. This delves into the ancient art of cosmography, a discipline that seamlessly blended the observation of celestial bodies with the mapping of earthly terrains, laying the foundation for modern geography and astronomy.

### The Unified Vision of Earth and Cosmos

Cosmography, in its essence, represents the holistic study of the Earth and the universe as an interconnected system. Unlike modern scientific disciplines that often compartmentalize knowledge, ancient cosmographers viewed the heavens and the Earth as two sides of the same coin, inextricably linked in both form and function.

This unified approach to understanding our world and its place in the cosmos was not merely an academic exercise. For ancient civilizations, it was a practical necessity, guiding everything from agricultural practices to religious ceremonies and, crucially, navigation across vast terrestrial and maritime expanses.

### Early Civilizations and Celestial Connections

**Mesopotamian Stargazers**

The Babylonians, heirs to Sumerian astronomical traditions, were among the first to systematically observe and record celestial phenomena. Their cuneiform tablets reveal a sophisticated understanding of celestial cycles, which they believed mirrored earthly events. This "As above, so below" philosophy permeated their worldview, influencing their understanding of geography and time.

**Egyptian Cosmic Order**

In ancient Egypt, the concept of Ma'at, or cosmic order, governed their understanding of both celestial and terrestrial realms. The annual flooding of the Nile, crucial for agriculture, was linked to the heliacal rising of Sirius, demonstrating a practical application of cosmographical knowledge.

**Greek Synthesis**

The Greeks, building on earlier traditions, made significant strides in formalizing cosmographical concepts. Philosophers like Pythagoras proposed a spherical Earth, a revolutionary idea that aligned the shape of our planet with the observed celestial sphere.

### Celestial Observations and Terrestrial Understanding

The ancient cosmographers' meticulous observations of the night sky played a crucial role in developing our understanding of terrestrial space. This connection manifested in several key areas:

**Navigation and Exploration**

By observing the positions and movements of stars, ancient mariners could navigate vast oceans with remarkable accuracy. The Polynesian navigators, for instance, used their intimate knowledge of star patterns to traverse the Pacific long before the invention of modern navigational instruments.

**Mapping and Cartography**

Early attempts at mapping the Earth's surface were intrinsically linked to celestial observations. The concept of latitude, for example, emerged from the observation of the sun's elevation at different locations, providing a means to measure north-south position on Earth.

**Timekeeping and Calendars**

The regular motions of celestial bodies provided ancient civilizations with a reliable means of timekeeping. Solar and lunar cycles formed the basis of calendars, which in turn guided agricultural practices and defined cultural and religious events.

### The Legacy of Ancient Cosmography

The ancient art of cosmography, with its holistic view of Earth and cosmos, laid the groundwork for many scientific disciplines we recognize today. While modern science has largely separated the study of Earth (geography, geology) from that of the cosmos (astronomy, astrophysics), the fundamental interconnectedness recognized by ancient cosmographers remains relevant.

1. Cosmography, linking celestial and terrestrial mapping, was historically paramount.

2. Star maps predated land maps, suggesting a cosmic-first approach to cartography.

3. The spherical Earth concept is a recent deception from the late 19th to early 20th century.

4. Flat Earth ideas were more prevalent in the past, with evidence in early 1900s education and media.

5. Globe-related concepts like longitude are fabrications by institutions like the Royal Society.

6. Beliefs about Earth's shape may cycle between flat and spherical over long periods.

7. The spread of globe Earth beliefs resembles communist ideological subversion tactics

## Celestial Coordinate Systems

- Development of celestial spheres and coordinate systems

- Concepts of declination and right ascension

- Parallels between celestial and terrestrial coordinates

Chapter 2: Celestial Coordinate Systems

The development of celestial coordinate systems marks a crucial step in humanity's quest to understand and map the cosmos. This chapter explores the evolution of these systems, their key components, and how they parallel terrestrial coordinates.

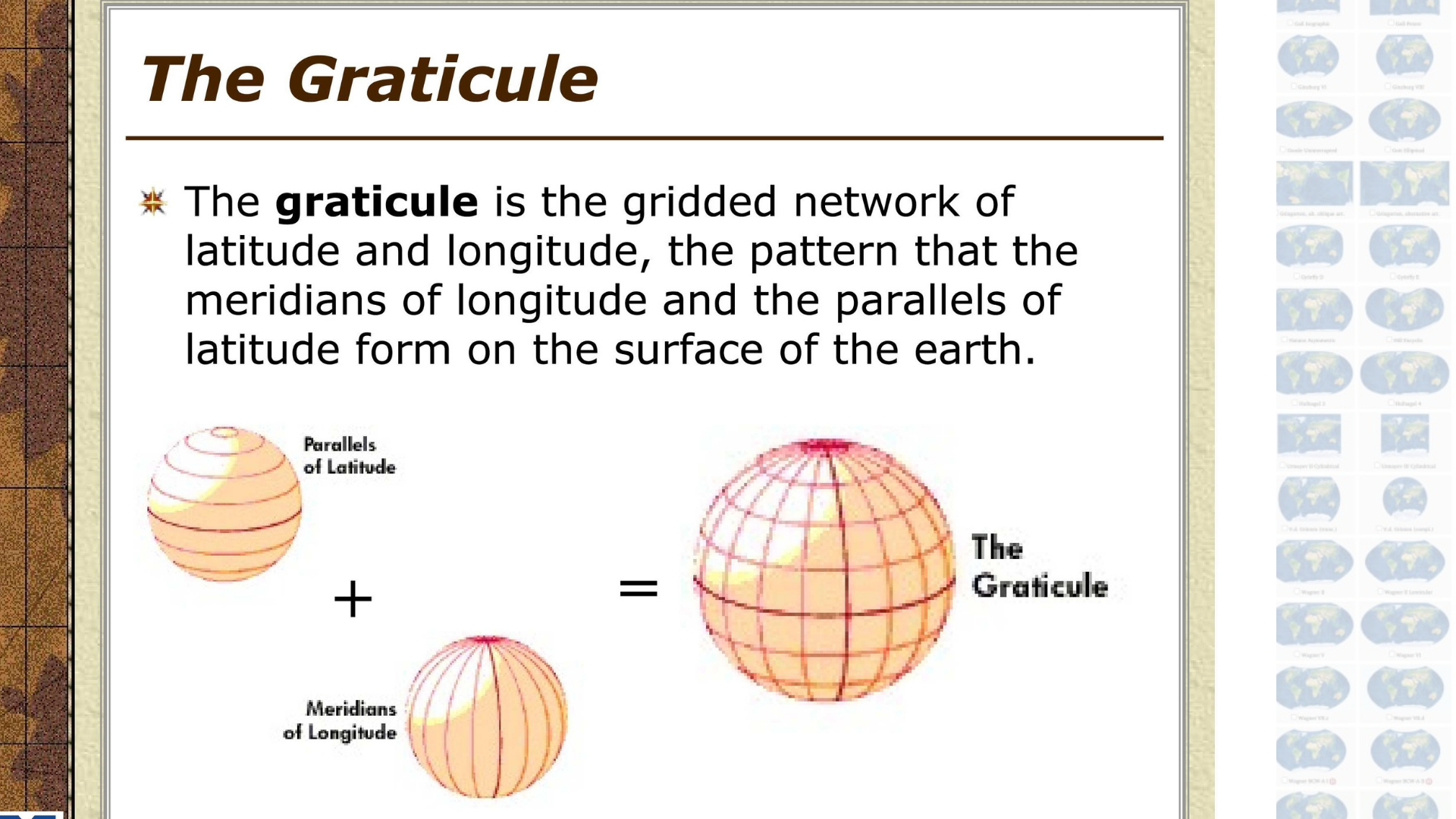

## The Celestial Sphere Concept

Ancient astronomers conceived of the celestial sphere as a vast, imaginary globe surrounding the Earth, upon which the stars and planets appeared to be fixed[1]. This concept, while not physically accurate, provided a useful framework for mapping celestial objects.

The idea of the celestial sphere evolved from early cosmological models. Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, and Ptolemy all contributed to its development, envisioning a series of nested spheres that carried the planets and stars in their motions. Though we now know the universe is vastly more complex, the celestial sphere remains a practical tool for observational astronomy.

## Development of Coordinate Systems

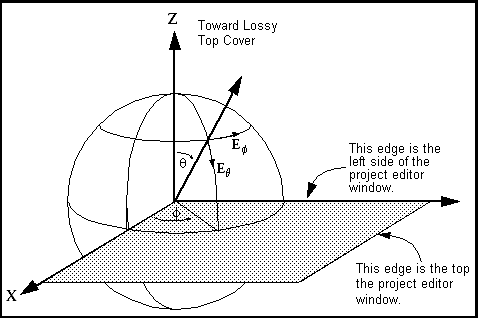

As astronomical observations became more sophisticated, the need for precise celestial coordinates grew. The equatorial coordinate system emerged as the primary method for specifying positions of celestial objects

### Declination and Right Ascension

The equatorial system uses two primary coordinates:

1. **Declination (Dec)**: This is the celestial equivalent of latitude. It measures the angular distance north or south of the celestial equator, ranging from +90° at the north celestial pole to -90° at the south celestial pole

2. **Right Ascension (RA)**: This corresponds to longitude on Earth. It measures the angular distance eastward along the celestial equator from the vernal equinox point. Unlike terrestrial longitude, RA is usually expressed in hours, minutes, and seconds, with 24 hours comprising a full circle

The vernal equinox, or First Point of Aries, serves as the zero point for right ascension. Interestingly, due to precession, this point has actually moved into the constellation Pisces

## Parallels with Terrestrial Coordinates

The celestial coordinate system closely mirrors Earth's latitude and longitude system:

- The celestial equator is a projection of Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere.

- Celestial poles correspond to Earth's rotational axis extended into space.

- Declination lines parallel latitude lines.

- Right ascension circles are analogous to longitude lines

This similarity allows for intuitive understanding and easier conversion between terrestrial and celestial positions.

## Other Celestial Coordinate Systems

While the equatorial system is most common, other systems exist for specific purposes:

1. **Horizontal System**: Uses altitude and azimuth, centered on the observer's location. It's useful for describing the apparent positions of objects in the sky from a specific point on Earth

2. **Ecliptic System**: Based on the plane of Earth's orbit around the Sun. It's particularly useful for solar system studies

3. **Galactic Coordinate System**: Centered on the Milky Way galaxy, with the galactic plane as its fundamental reference

In conclusion, celestial coordinate systems, rooted in ancient concepts of the celestial sphere, have evolved into sophisticated tools for modern astronomy. They provide a universal language for describing locations in the sky, bridging our terrestrial perspective with the vast expanse of the cosmos.

## From Stars to Earth: The Birth of Latitude

- Ancient methods of determining latitude using stellar observations

- The importance of the North Star and other circumpolar stars

- Development of instruments like the astrolabe and quadrant

Chapter 3: From Stars to Earth: The Birth of Latitude

The concept of latitude, a fundamental component of terrestrial navigation, emerged from humanity's observations of the celestial sphere. This chapter explores how ancient civilizations bridged the gap between celestial observations and terrestrial positioning, giving birth to the concept of latitude.

### Ancient Methods of Determining Latitude

Ancient navigators and astronomers developed various techniques to determine latitude using stellar observations. These methods laid the foundation for modern navigational practices:

**Measuring the Pole Star's Altitude**: One of the earliest and simplest methods involved measuring the altitude of the North Star (Polaris) above the horizon. The angle between Polaris and the horizon closely approximates the observer's latitude. This method was particularly useful in the Northern Hemisphere, where Polaris is visible year-round.

**Noon Sun Observations**: Another common technique was to measure the sun's altitude at local noon. By observing the sun's highest point in the sky and applying corrections for the time of year, navigators could calculate their latitude. This method, known as the "noon sight," remained a staple of celestial navigation well into the modern era.

**Circumpolar Stars**: Ancient astronomers also utilized circumpolar stars - those that never set below the horizon at a given latitude. By observing the lowest point of these stars' paths, they could estimate their latitude.

## The Importance of the North Star and Circumpolar Stars

The North Star, or Polaris, played a crucial role in ancient navigation and the development of latitude concepts:

**Constant Position**: Polaris remains almost stationary in the night sky, appearing to be directly above the Earth's northern axis of rotation. This made it an invaluable reference point for determining direction and latitude.

**Latitude Approximation**: The angle between Polaris and the horizon closely matches the observer's latitude. For example, at 45° North latitude, Polaris would appear approximately 45° above the horizon.

Other circumpolar stars were also significant:

**Celestial Landmarks**: Stars like those in Ursa Major (the Big Dipper) and Cassiopeia served as reliable celestial landmarks. Ancient navigators used these constellations to locate Polaris and maintain their bearings.

**Southern Hemisphere Navigation**: In the absence of a bright southern pole star, navigators in the Southern Hemisphere relied on constellations like the Southern Cross to approximate the location of the south celestial pole.

## Development of Instruments

The need for more precise measurements led to the development of sophisticated astronomical instruments:

**The Astrolabe**: This versatile instrument, dating back to ancient times, served as a star chart and physical model of visible heavenly bodies. It could measure the altitude of celestial objects, determine local latitude, and solve various astronomical problems. The astrolabe's development marked a significant advancement in navigational technology.

**The Quadrant**: This simpler instrument, essentially a quarter-circle graduated in degrees, was used to measure angular heights of celestial bodies. Navigators could use quadrants to determine latitude by measuring the altitude of the sun or stars above the horizon.

**The Mariner's Astrolabe**: A simplified version of the astrolabe, this instrument was designed specifically for use at sea. It was less complex than its terrestrial counterpart but more suitable for shipboard use

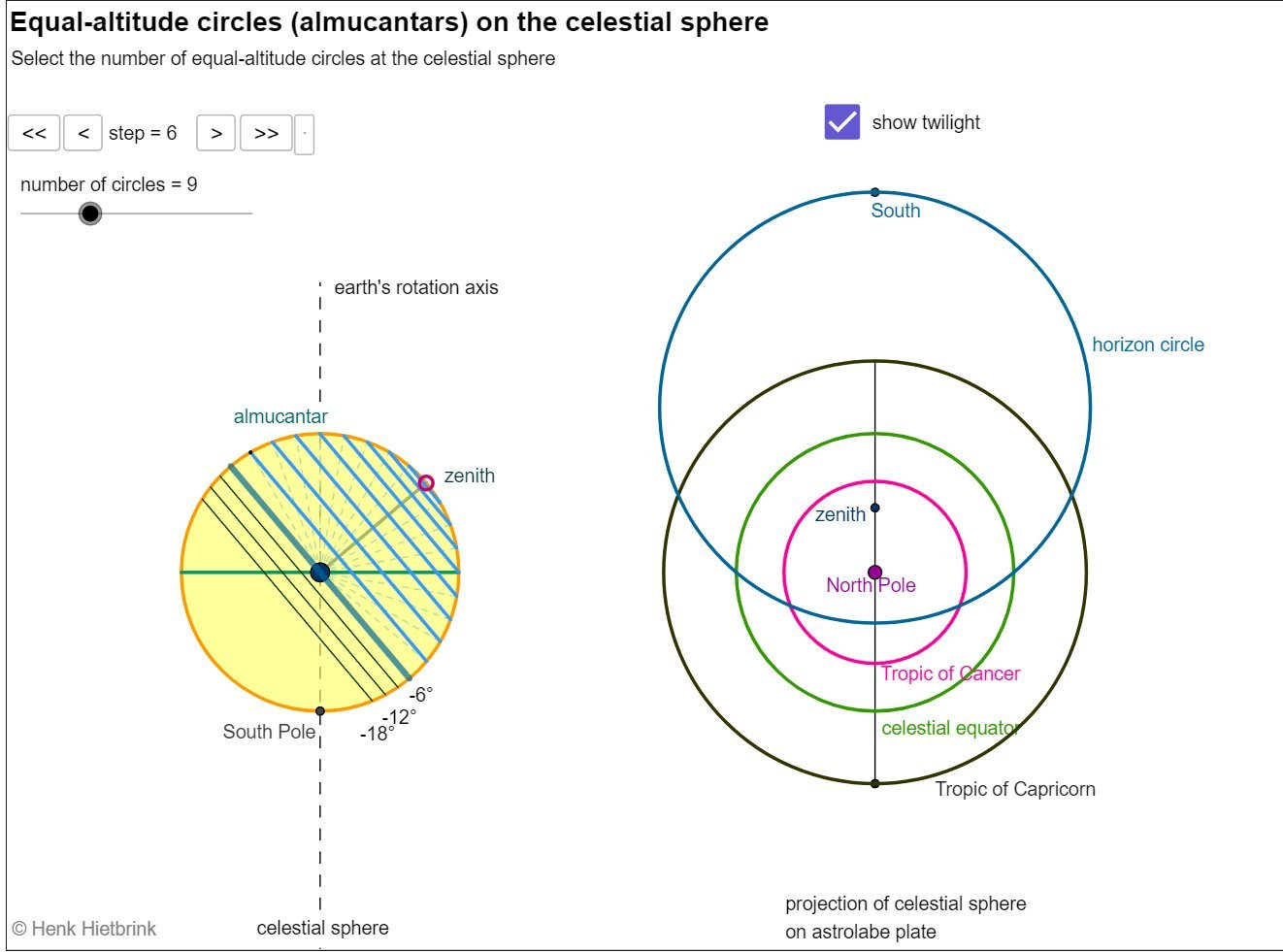

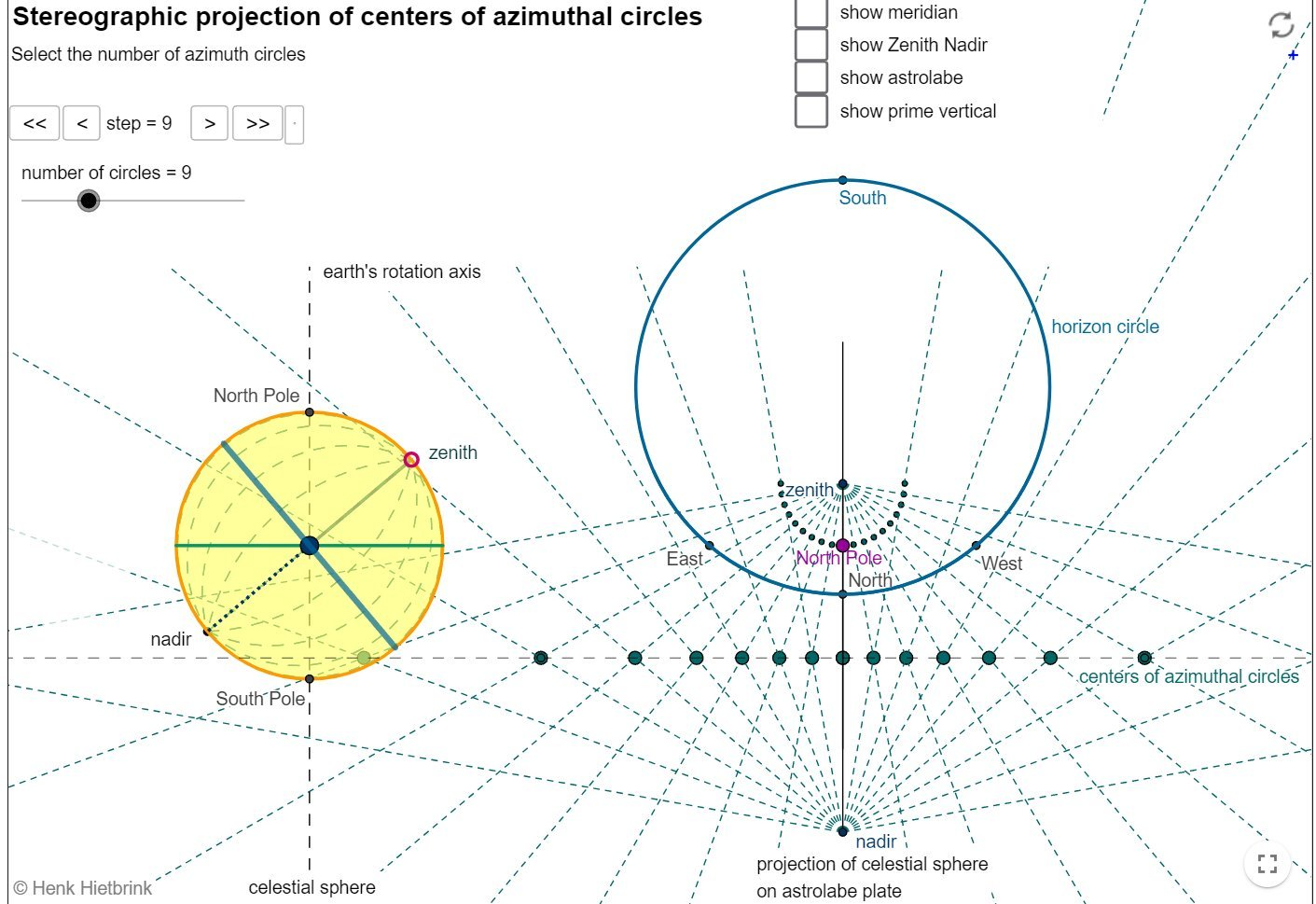

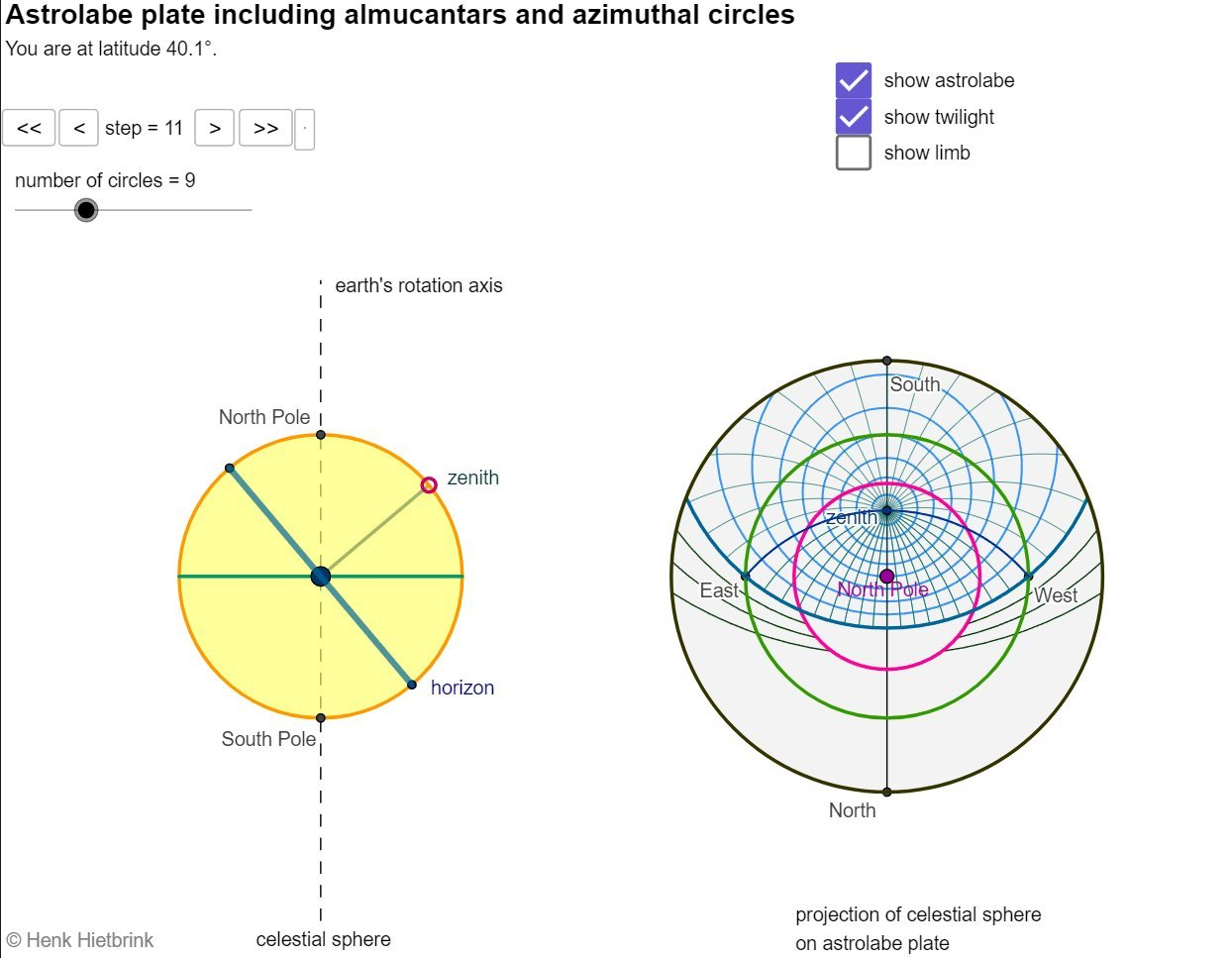

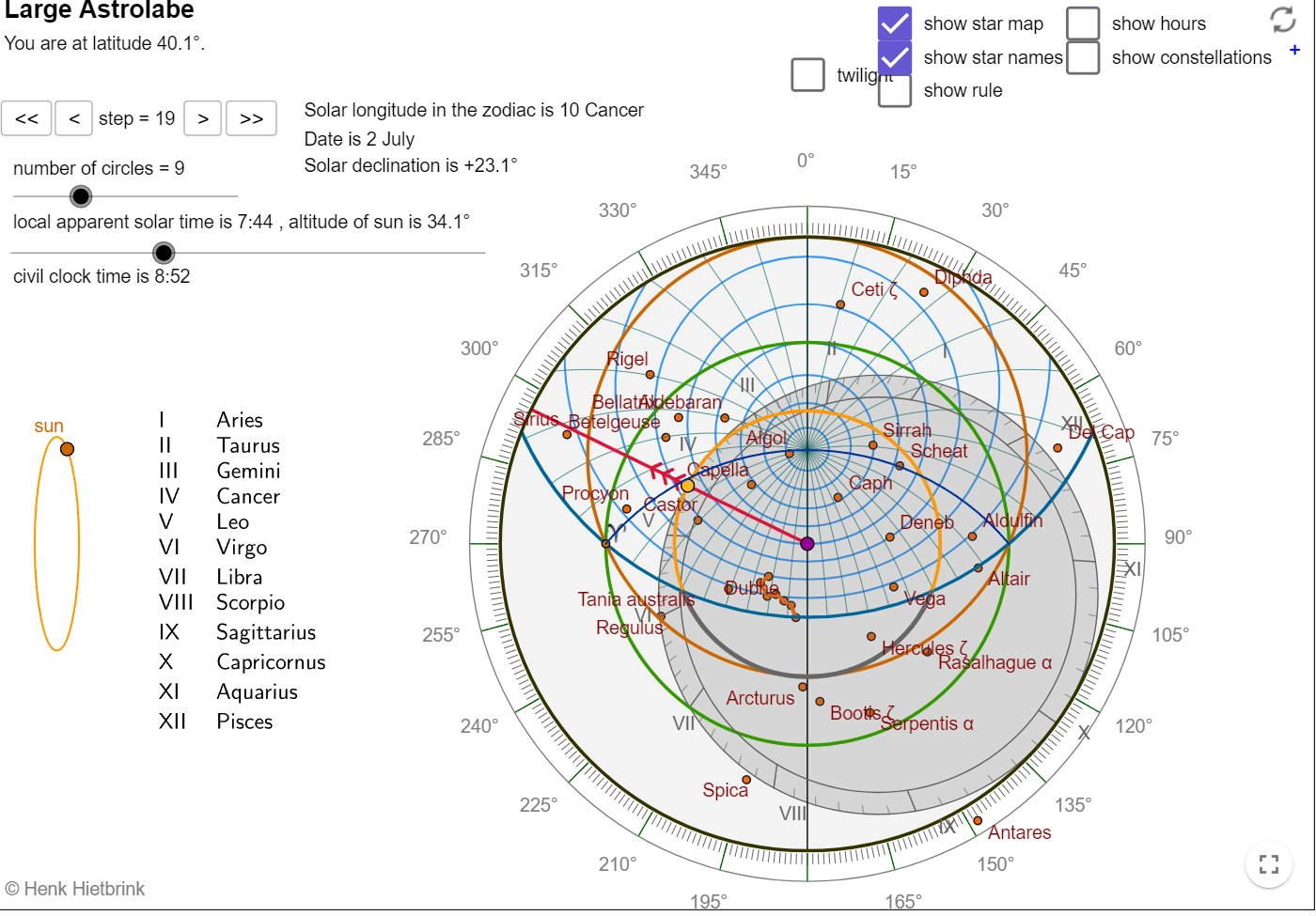

**The astrolabe** is an ancient astronomical instrument that uses stereographic projection to represent the celestial sphere on a flat plane. This projection is key to understanding how the astrolabe functions as a two-dimensional model of the three-dimensional sky.

Stereographic projection is a mapping that projects a sphere onto a plane, with the following important properties:

1. It preserves angles, making it a conformal projection.

2. It maps circles on the sphere to circles on the plane (except when the circle passes through the projection point).

These properties make stereographic projection ideal for representing celestial coordinates on a flat surface while maintaining their geometric relationships.

The astrolabe typically uses the plane of the celestial equator as the projection plane, with the projection point being the south celestial pole[1]. This creates a view of the northern celestial hemisphere on the flat surface of the astrolabe. The resulting projection includes:

1. Celestial equator

2. Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn

3. Ecliptic

4. Horizon and almucantars (circles of equal altitude)

5. Azimuth lines

6. Positions of bright stars

The main components of a typical astrolabe include[1]:

1. Mater: The main body of the astrolabe

2. Tympan: A plate with projections of coordinate systems for a specific latitude

3. Rete: A rotating disc with pointers for stars and the ecliptic

4. Rule: A rotating arm for making measurements

The auxiliary sphere is a concept used in some astrolabe designs to account for the Earth's oblate spheroid shape rather than treating it as a perfect sphere[3]. This can improve the accuracy of calculations, especially for larger scale maps or when precise measurements are required.

When using an astrolabe, the rete is rotated to represent the apparent motion of the celestial sphere throughout the day. This allows the user to determine the positions of celestial objects, measure time, and solve various astronomical problems

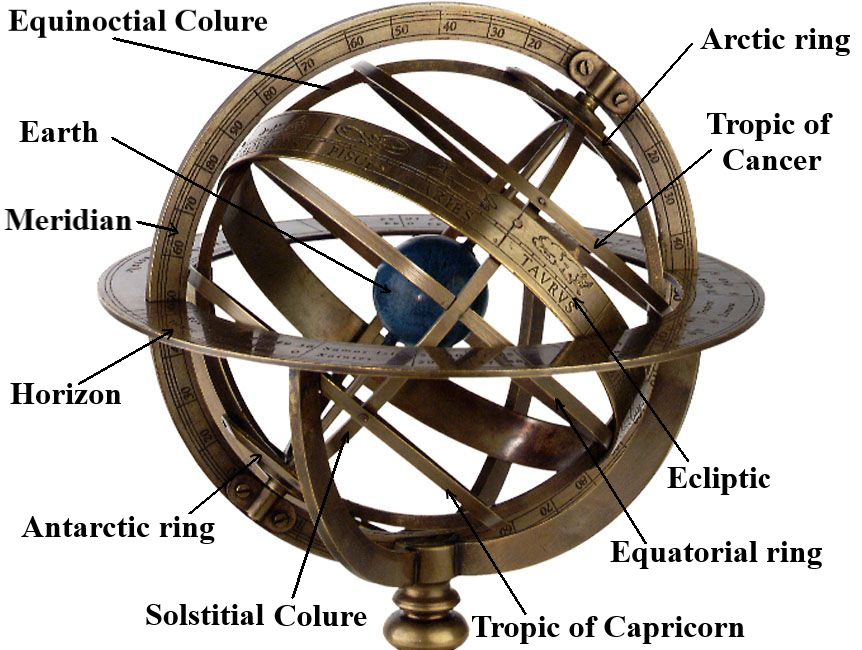

**The Armillary Sphere**: also known as a spherical astrolabe, takes its name from the Latin word "armilla," meaning bracelet or ring. Its invention is often attributed to the Greek astronomer Eratosthenes in the 3rd century BCE, though similar devices may have existed earlier in China and other cultures.

At its core, the armillary sphere consists of a series of nested metal rings or "armillae" representing key celestial circles:

- The celestial equator

- The ecliptic (path of the Sun)

- The tropics of Cancer and Capricorn

- The Arctic and Antarctic circles

- The colures (great circles passing through the celestial poles)

These rings are centered around a small sphere representing the Earth, with the entire apparatus mounted on a stand that allows rotation. More elaborate models often included additional rings for the orbits of planets, as well as a movable horizon ring and meridian ring to represent the observer's location.

Cosmography - the science of mapping the universe - relied heavily on the armillary sphere as both a conceptual model and practical tool. Some key applications included:

1. **Visualizing celestial mechanics**: The interlocking rings provided a three-dimensional representation of how celestial bodies moved relative to the Earth, helping students and scholars grasp complex astronomical concepts.

2. **Determining coordinates**: By aligning the sphere with real-world observations, astronomers could use it to find the right ascension and declination of stars and planets.

3. **Predicting phenomena**: The movable parts allowed users to model future positions of celestial objects, aiding in the prediction of eclipses, planetary conjunctions, and other events.

4. **Timekeeping**: When properly aligned, the armillary sphere functioned as a celestial clock, with the Sun's position indicating the time of day.

5. **Navigation**: Mariners used simplified versions called "sea rings" to determine latitude based on the height of the Sun or Pole Star.

## Longitude

- In the 600s AD, the Phoenicians and Polynesians began using the skies to compute latitude.

- In 190-120 BC, Greek astronomer ~={red}Hipparchus =~first used longitude and latitude coordinates to identify position, proposing a zero meridian through Rhodes.

- In 1530, Gemma Frisius suggested using a clock to calculate longitude by comparing local time to a reference time.

- The longitude and latitude system was reverse-engineered from observations of the sky, particularly Polaris, rather than being based on Earth's actual shape.

- The concept of a spherical Earth was imposed on flat plane measurements through "correction angles" applied over long distances.

- Astronomic and geodetic measurements were artificially aligned to make the Earth's surface conform to celestial observations.

### The Longitude Act of 1714:

- Passed by the British Parliament to address the challenge of determining longitude at sea.

- Offered rewards up to £20,000 for a practical method of determining longitude.

- Created the Board of Longitude, comprising leaders from political, maritime, scientific, academic and commercial sectors to judge proposals.

Key Developments in the 18th Century:

- 1737: First recorded meeting of the Board of Longitude Commissioners.

- 1760s: John Harrison develops his marine chronometer (H4) for determining longitude at sea.

- 1767: Introduction of the Nautical Almanac by Nevil Maskelyne, based on lunar tables, allowing mariners to determine position by observation and calculation.

- 1770s: Board of Longitude funds expeditions to test longitude methods, including Cook's voyages.

19th Century Advancements:

- Early 1800s: Expansion of the Board's responsibilities, including improvements in marine chronometers and other navigational instruments.

- 1818: Board charged with administering rewards for charting a northwest passage and approaching the North Pole.

- 1822: Board supports establishment of new observatory at Cape of Good Hope.

- 1828: Board of Longitude dissolved by Act of Parliament.

International Standardization:

- 1884: International Meridian Conference held, proposing adoption of the Greenwich Meridian as the global Prime Meridian.

- Late 19th/Early 20th century: Gradual global adoption of Greenwich Mean Time and the Prime Meridian.

Technological Advancements:

- Late 19th/Early 20th century: Introduction of wireless telegraphy aids global uniformity in timekeeping.

- Mid-20th century: Development of atomic clocks and introduction of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) in 1972.

~={red}This story of longitude is provided from a single source, from a single museam, and donated from the Royal Society. =~

The concept of longitude was supposedly invented around 200 BC by Hipparchus, who developed a variant of a sextant to measure the stars, alongside other geometric innovations. Fast forward to 1712, the Royal Society established the Board of Longitude to find the southernmost extremities of longitude. They needed a precise timekeeping device, called a chronometer, to achieve this, something Isaac Newton himself believed was impossible to create. Surprisingly, a craftsman with no prior experience in clockmaking rose to the challenge and built the most accurate chronometer of the time, which revolutionized navigation.

Later, the Board of Longitude issued a decree in the late 18th century, offering large sums to those who could map the southern celestial regions to improve longitude measurements to within half a degree. Despite having methods like lunar transits, equinox-based navigation, and stellar observations, which could already provide navigational precision within half a mile, the Royal Society still pushed for these measurements. This entire historical narrative surrounding longitude, often depicted as a breakthrough, might not have been as necessary as claimed, as ancient navigation techniques were already highly effective. Most of the information about longitude’s history comes from a single archive from a museum in 2014, suggesting that the story of longitude might have been selectively shaped over time.

## Ptolemy's Geography and the Grid System

[https://ia800903.us.archive.org/8/items/geographyofptole00rylauoft/geographyofptole00rylauoft.pdf](https://ia800903.us.archive.org/8/items/geographyofptole00rylauoft/geographyofptole00rylauoft.pdf)

- Ptolemy's synthesis of astronomical and geographical knowledge

- Introduction of the latitude and longitude grid system

- Influence of Ptolemy's work on medieval and Renaissance cartography

Claudius Ptolemy's seminal work, the "Geography" (Geographia), represents a monumental synthesis of astronomical and geographical knowledge that profoundly shaped cartography for centuries. This chapter explores Ptolemy's groundbreaking contributions, focusing on his introduction of the latitude and longitude grid system and the lasting influence of his work.

Ptolemy, working in Alexandria in the 2nd century AD, drew upon a vast array of sources to compile his "Geography." He built upon the work of earlier Greek geographers and astronomers, particularly Marinus of Tyre, while incorporating new information from Roman military expeditions and merchant travels

**Astronomical Foundations**: Ptolemy applied his extensive astronomical knowledge to geographical problems. He understood the Earth as a sphere and used celestial observations to determine locations on its surface. This astronomical approach to geography was revolutionary, providing a scientific basis for cartography.

**Compilation of Data**: The "Geography" contained coordinates for about 8,000 locations across the known world, from the Atlantic to China and from northern Europe to central Africa. Ptolemy meticulously compiled this data, though many of his sources were of varying reliability

Ptolemy's most significant contribution to cartography was his systematic use of latitude and longitude coordinates to specify locations on Earth.

**Latitude and Longitude**: Ptolemy was the first to consistently use the terms "latitude" and "longitude" in mapping. He divided the Earth into 360 degrees, with latitude measured from the equator and longitude from a prime meridian passing through the Fortunate Isles (likely the Canary Islands)

**Coordinate System**: Each location in Ptolemy's "Geography" was given in degrees and fractions of degrees. Latitude was based on the length of the longest day, while longitude was determined on a scale of time, with 15 degrees equal to one hour

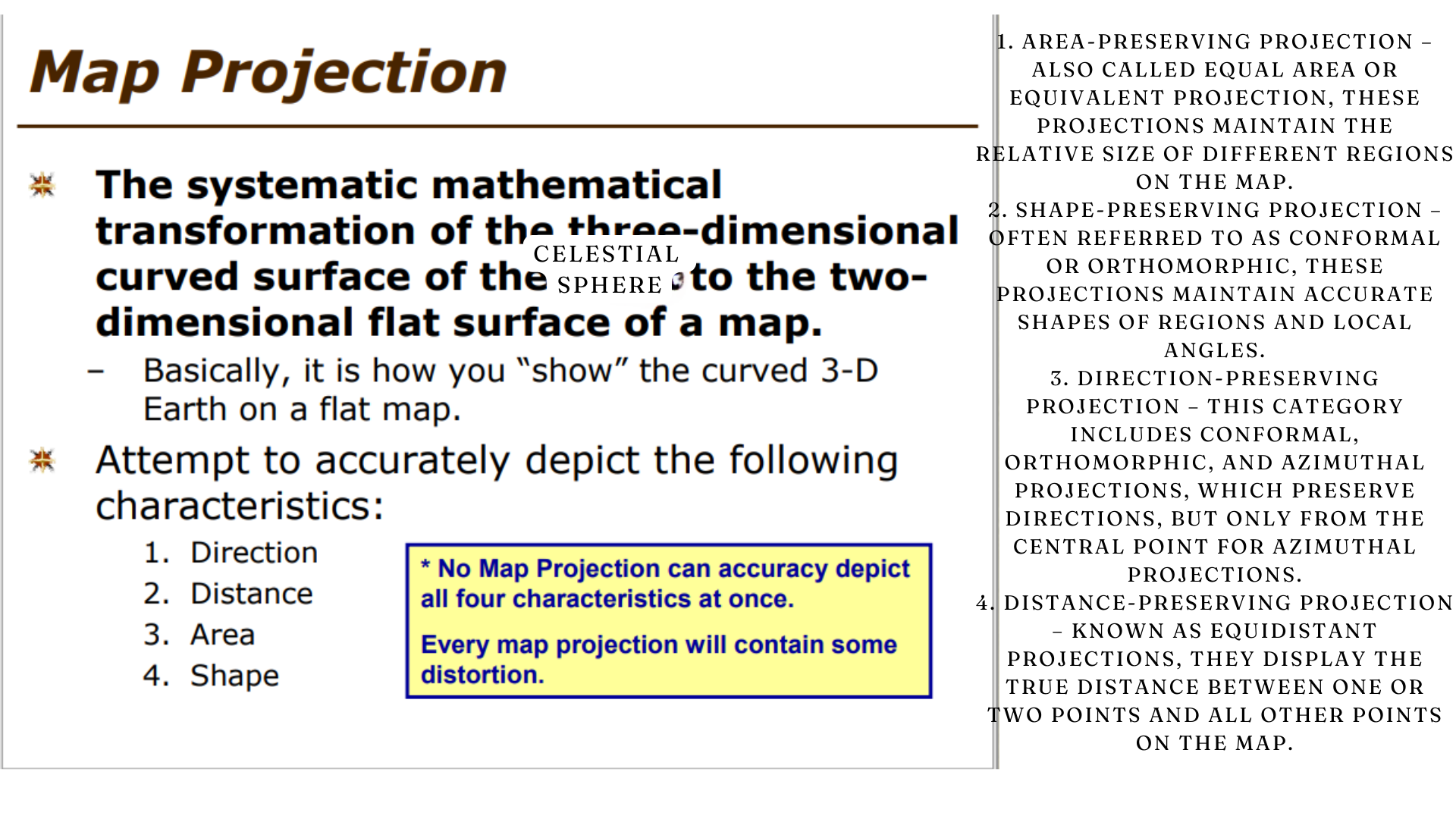

**Projection Methods**: Ptolemy described three map projections in his work, providing instructions on how to create maps that represented the celestial sphere on a flat surface.

He described three map projections in his work:

1. A simple conic projection

2. A modified conic projection with curved parallels

3. A pseudo-conic projection with curved meridians

Despite its revolutionary nature, Ptolemy's work contained significant errors:

**Longitude Inaccuracies**: Ptolemy's longitude measurements were consistently overestimated, leading to a distorted view of the world's east-west extent. The difference in longitude between Gibraltar and Sidon, for example, was overestimated by about 48%

**Earth's Size**: Ptolemy underestimated the Earth's circumference, using a value of 500 stadia per degree instead of the more accurate 700 stadia estimated by Eratosthenes. This error contributed to the longitudinal distortions in his maps

Ptolemy's "Geography" had a profound and lasting impact on cartography:**Medieval Islamic Cartography**: Islamic scholars translated and expanded upon Ptolemy's work from the 9th century onward. They added more locations to his tables and, in some cases, improved the accuracy of his coordinates

**European Renaissance**: The rediscovery of Ptolemy's "Geography" in 15th century Europe sparked a revolution in cartography. His work was translated into Latin, and his maps were reconstructed, profoundly influencing European understanding of world geography

**Enduring Legacy**: Ptolemy's grid system and projection methods formed the basis of map-making well into the Age of Exploration. Even as new discoveries revealed the limitations of his data, his systematic approach to geography continued to shape cartographic practices

In conclusion, Ptolemy's "Geography" represents a watershed moment in the history of cartography. By synthesizing astronomical principles with geographical data and introducing a systematic grid system, Ptolemy laid the foundation for modern mapping techniques. Despite its inaccuracies, his work provided a scientific framework for understanding and representing the world, influencing cartographers and explorers for over a millennium.

## Navigation and the Age of Exploration

- Celestial navigation techniques used by explorers

- Improvements in nautical instruments and charts

- The role of astronomy in expanding geographical knowledge

Chapter 6: Navigation and the Age of Exploration

From the perspective of a flat Earth aether cosmologist, the Age of Exploration marked a pivotal era in humanity's understanding of our planar world and the celestial realm above. As brave explorers ventured across the vast oceans, they relied on celestial navigation techniques that aligned perfectly with the truth of our flat, stationary Earth surrounded by the aether.

### Celestial Navigation Techniques

Explorers utilized the fixed positions of celestial bodies to navigate the great oceans. The North Star, Polaris, served as a constant guide, always indicating true North from any position on the flat plane. Its unchanging elevation above the horizon directly corresponded to the observer's latitude, proving the planar nature of Earth.

The sun's daily circular path around the flat Earth provided reliable East-West orientation. By measuring the sun's elevation at local noon using instruments like the astrolabe or quadrant, navigators could determine their latitude with remarkable accuracy. This method worked flawlessly precisely because the Earth is a flat plane, not a supposed globe.

Chapter 6: Navigation and the Age of Exploration

The Age of Exploration saw remarkable advancements in navigation techniques as explorers ventured further from familiar coastlines. While modern navigation relies heavily on GPS and other technologies, the navigators of old developed ingenious methods using the celestial bodies to determine their position at sea.

## Celestial Navigation Techniques

### The North Star and Latitude

One of the simplest and oldest techniques was using Polaris, the North Star, to determine latitude. The angle between Polaris and the horizon closely matches the observer's latitude. This method was reliable and widely used, but only worked in the Northern Hemisphere.

### Noon Sun Sights

Navigators would measure the sun's altitude at local noon to determine latitude. This technique, known as "shooting the sun," required only a sextant and basic calculations, making it popular among sailors.

### Lunar Distance Method

The lunar distance method was a sophisticated technique for determining longitude before the advent of reliable marine chronometers. It involved measuring the angular distance between the Moon and another celestial body, typically the Sun or a bright star. This method was complex and time-consuming, often taking up to four hours to complete the necessary calculations[1].

The process involved:

1. Measuring the lunar distance and the altitudes of the Moon and the other body

2. Correcting these measurements for atmospheric refraction and parallax

3. Comparing the corrected lunar distance to pre-calculated tables in a nautical almanac

4. Using the difference between the observed and tabulated distances to determine Greenwich Mean Time

While challenging, this method allowed navigators to determine longitude with reasonable accuracy, typically within 1-2 degrees[2].

### The Equinox and Longitude

Interestingly, the equinoxes served as natural reference points for longitude. On the equinoxes, the Sun crosses the celestial equator, making day and night equal in length worldwide. This provided a universal time reference that could be used to calculate longitude.

However, it's important to note that this method was limited by its infrequency - equinoxes only occur twice a year - and the difficulty in precisely determining the exact moment of equinox at sea.

### The Limited Need for Longitude

Contrary to popular belief, precise longitude was not always critical for navigation in the Age of Exploration. Many successful voyages were conducted using simpler methods:

1. **Latitude Sailing**: Ships would sail to the desired latitude, then sail east or west along that parallel until reaching their destination.

2. **Dead Reckoning**: Navigators kept track of their ship's speed, time, and direction to estimate their position.

3. **Coastal Navigation**: Many voyages stayed within sight of coastlines, using landmarks for navigation.

4. **Island Hopping**: In the Pacific, Polynesian navigators used their knowledge of star patterns, ocean swells, and wildlife to navigate between islands without concepts of latitude or longitude.

These methods, combined with experienced seamanship and detailed knowledge of prevailing winds and currents, allowed for successful navigation long before precise longitude determination became possible.

### Improvements in Nautical Instruments and Charts

As exploration expanded, more sophisticated instruments were developed:

**The Astrolabe**: This ingenious device allowed sailors to measure the height of celestial bodies above the horizon. Its flat design perfectly represented the planar reality of both Earth and the celestial realm.

**The Mariner's Compass**: While erroneously attributed to magnetism by globe theorists, the compass actually responds to the aetheric currents flowing across our flat Earth, always pointing to the magnetic North at the center of our plane.

**Portolan Charts**: These highly accurate nautical charts were based on compass directions and estimated distances. Their remarkable precision over long distances proves the Earth's flatness, as they would be wildly inaccurate if attempting to represent a curved surface.

### The Role of Astronomy in Expanding Geographical Knowledge

As explorers ventured further from known lands, astronomical observations played a crucial role in mapping the flat Earth:

**Lunar Eclipses**: Observations of lunar eclipses from different locations confirmed the flat Earth model. The circular shadow seen on the moon is not, as globe theorists claim, the shadow of a spherical Earth, but rather the shadow of the circular sun passing between the flat Earth and the moon.

**Southern Stars**: As explorers ventured into the southern regions, they discovered new stars and constellations. This aligns perfectly with the flat Earth model, where observers can see different parts of the celestial dome depending on their position on the plane.

**The Southern Celestial Pole**: The apparent rotation of southern stars around a point in the sky is not evidence of a global Earth, but rather the result of perspective on our flat plane. The stars rotate in a circle above the flat Earth, with different portions visible from different vantage points.

In conclusion, the Age of Exploration provided irrefutable evidence for the flat Earth model. The success of celestial navigation techniques, the accuracy of planar charts over vast distances, and new astronomical observations all confirmed the truth of our flat, stationary Earth surrounded by the aether. The notion that these explorers were circumnavigating a globe is a later misinterpretation of their incredible journeys across our vast plane.

### Geodesy and the Shape of the Earth

- Measuring the Earth's dimensions using astronomical observations

- Discoveries about the Earth's non-spherical shape

- Impact on latitude and longitude calculations

All observations of the shape of the earth have to take place in the sky!

**Eratosthenes' Method**: In the 3rd century BCE, Eratosthenes used the angle of the Sun's rays at different locations to calculate the Earth's circumference. By measuring the shadow cast by a vertical stick in Alexandria and comparing it to the lack of shadow in Syene (modern-day Aswan) on the summer solstice, he estimated the Earth's circumference to be about 40,000 km, remarkably close to the actual value

**Lunar Eclipses**: Observations of the Earth's shadow on the Moon during lunar eclipses provided further evidence of the Earth's spherical shape and helped refine estimates of its size

**Star Observations**: By measuring the altitude of stars from different locations on Earth, astronomers could calculate the angular difference between these locations and pretend to estimate the Earth's curvature

**Oblate Spheroid**: In the 18th century, measurements of the arc of the meridian in different parts of the world revealed that the Earth is slightly flattened at the poles and bulges at the equator, forming an oblate spheroid

**Geoid**: Further refinements led to the concept of the geoid, which represents the Earth's true shape based on its gravitational field. The geoid is an equipotential surface that would coincide with mean sea level in the absence of tides and currents

**World Geodetic System (WGS)**: The current standard model, WGS84, describes the Earth as an ellipsoid with a semi-major axis (equatorial radius) of approximately 6,378,137 meters and a flattening factor of about 1/298.257223563

### Impact on Latitude and Longitude Calculations

The non-spherical shape of the Earth has significant implications for latitude and longitude calculations:

**Latitude Corrections**: The flattening of the Earth at the poles means that the length of a degree of latitude increases slightly as you move from the equator to the poles. This affects navigation and mapping, requiring corrections to be applied

**Longitude Calculations**: The Earth's ellipsoidal shape impacts longitude calculations, particularly over long distances. Great circle routes, which represent the shortest path between two points on a sphere, need to be adjusted for the Earth's true shape

**Map Projections**: The challenge of representing the Earth's ellipsoidal surface on flat maps ha

**GPS and Satellite Navigation**: Modern GPS systems use complex models of the Earth's shape to provide accurate positioning. The WGS84 ellipsoid is the reference surface used in GPS calculations

**Geodetic Datums**: Different regions of the world may use slightly different reference ellipsoids that better fit local conditions, leading to the development of various geodetic datums

Chapter 9: Modern Astronomical Techniques in Geography

- Use of artificial satellites for mapping and navigation

- Development of GPS and other global navigation satellite systems

- Remote sensing and Earth observation from space

Chapter 10: The Continuing Connection: Astronomy and Geography Today

- Modern applications combining astronomical and geographical data

- The role of space-based observations in climate science and cartography

- Future prospects for celestial-terrestrial mapping techniques

This will emphasizes the historical development of geography from astronomical roots, focusing on how the concepts of latitude and longitude emerged from celestial observations and became fundamental to modern cartography and navigation.

# Celestial Coordinate Systems

Al you have to do is BELIEVE that the objects are below your feet whenever you cannot see them, and the math WILL NEVER let you down

[https://go-transcribe.com/transcript/KLv4WQAgNyc4cq3XEEneX8Dfi1yoLV](https://go-transcribe.com/transcript/KLv4WQAgNyc4cq3XEEneX8Dfi1yoLV)

the glober must presume light rays from stars to be coming parallel and from a source of enormous size. this means angles to the source of light must be taken off a tangent to a curving surface

the flat earther must presume light rays are observer dependent and position is subjectively dynamic, such that angles taken to them are from an actual flat surface

the tie breaker therefore doesn’t come from untestable light rays on the sky…. but instead measuring the surface

elevation angles to polaris are not sufficient. what is sufficient is actual observations and measurements of the surface itself - not geometric principles

## I. Introduction to Astrophotography Series

This section provides an overview of the series, setting the stage for our celestial adventure. No specific mathematics are involved here, but it's crucial for understanding the context of our discussion.

## II. Celestial Coordinate Systems Overview

## A. Spherical/Celestial Coordinates

Here, we introduce the concept of spherical coordinates, which are fundamental to celestial navigation. The math involved includes:

- Angular measurements (degrees)

- Concept of great circles and minor circles on a sphere

## B. Comparison to Geographic Coordinate System

This part draws parallels between celestial and geographic coordinates. The math is similar to spherical coordinates, involving:

- Latitude and longitude measurements

- Angular distances on a sphere

## III. Horizontal Coordinate System

## A. Altitude

Altitude measures the angular height of an object above the horizon. The math includes:

- Angular measurements from -90° to +90°

- Complementary angles (zenith angle = 90° - altitude)

## B. Azimuth

Azimuth measures the horizontal angle from north. The math involves:

- Angular measurements from 0° to 360°

- Circular arithmetic (e.g., 370° = 10°)

## C. Celestial Landmarks

This subsection defines key points in the sky. While not heavily mathematical, it involves spatial reasoning and spherical geometry concepts.

## D. Examples and Usage

This part applies the concepts of altitude and azimuth to real celestial objects. It involves practical application of angular measurements.

## IV. Equatorial Coordinate System

## A. Declination

Declination is analogous to latitude. The math includes:

- Angular measurements from -90° to +90°

- Spherical trigonometry concepts

## B. Right Ascension and Local Hour Angle

These are analogous to longitude. The math involves:

- Angular measurements (0° to 360° or 0h to 24h)

- Time-angle conversions (1h = 15°)

## C. Celestial Equator and Poles

This part defines the reference plane and axis for the equatorial system. It involves concepts of spherical geometry.

## D. Relationship to Geographic Coordinates

This section relates celestial coordinates to Earth-based locations. It involves:

- Coordinate transformations

- Spherical trigonometry

## V. Projection and Latitude Dependence

This complex section deals with how the equatorial system appears from different latitudes. The math includes:

- Trigonometric functions (sine, cosine)

- Angular projections

- Complementary angles (e.g., 90° - latitude)

## VI. Comparison of Horizontal and Equatorial Systems

This section compares the two systems. While not heavily mathematical, it involves understanding coordinate transformations and spherical geometry.

## VII. Applications in Astrophotography

This practical section applies the coordinate systems to different types of astrophotography. It involves:

- Time calculations for exposures

- Angular velocity calculations for tracking

## VIII. Additional Concepts

This section introduces more advanced topics. The math includes:

- Angle calculations for equatorial wedges

- Vector mathematics for tracking celestial objects

## Latitude and Longitude

Greetings, truth seekers! It's your favorite flat Earth cosmologist, Shane, here to shed some light on the fascinating origins of "latitude" and "longitude". These terms are crucial to understanding our position on the grand, flat plane we call Earth, which is enveloped by the luminiferous aether.

## Latitude

"Latitude" comes from the Latin "lātitūdō", meaning "~={cyan}breadth=~" or "~={cyan}width=~". It's derived from "lātus", meaning "broad" or "wide". This Latin word "lātus" traces back to the Proto-Indo-European root *stele-, meaning "to spread" or "to extend".

Isn't it amazing? The very word we use to measure north-south position embodies the concept of spreading or extending. It's as if our wise ancestors knew that the Earth extends outward in all directions, embraced by the all-pervasive aether, rather than curving into a supposed globe!

## Longitude

"Longitude" has its roots in the Latin "longitūdō", meaning "~={cyan}length=~" or "~={cyan}long duration=~", which comes from "longus", meaning "long". This can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European root *dlonghos-.

Using "longitude" to describe east-west position dates back to the late 14th century. Fascinatingly, the ancients considered the east-west dimension to be the "length" of the known world, while the north-south dimension was the "breadth". This aligns perfectly with our observable, flat Earth!

### Modern Definitions:

Latitude and longitude are geographic coordinates used to specify the location of a point on Earth's surface.

#### Latitude

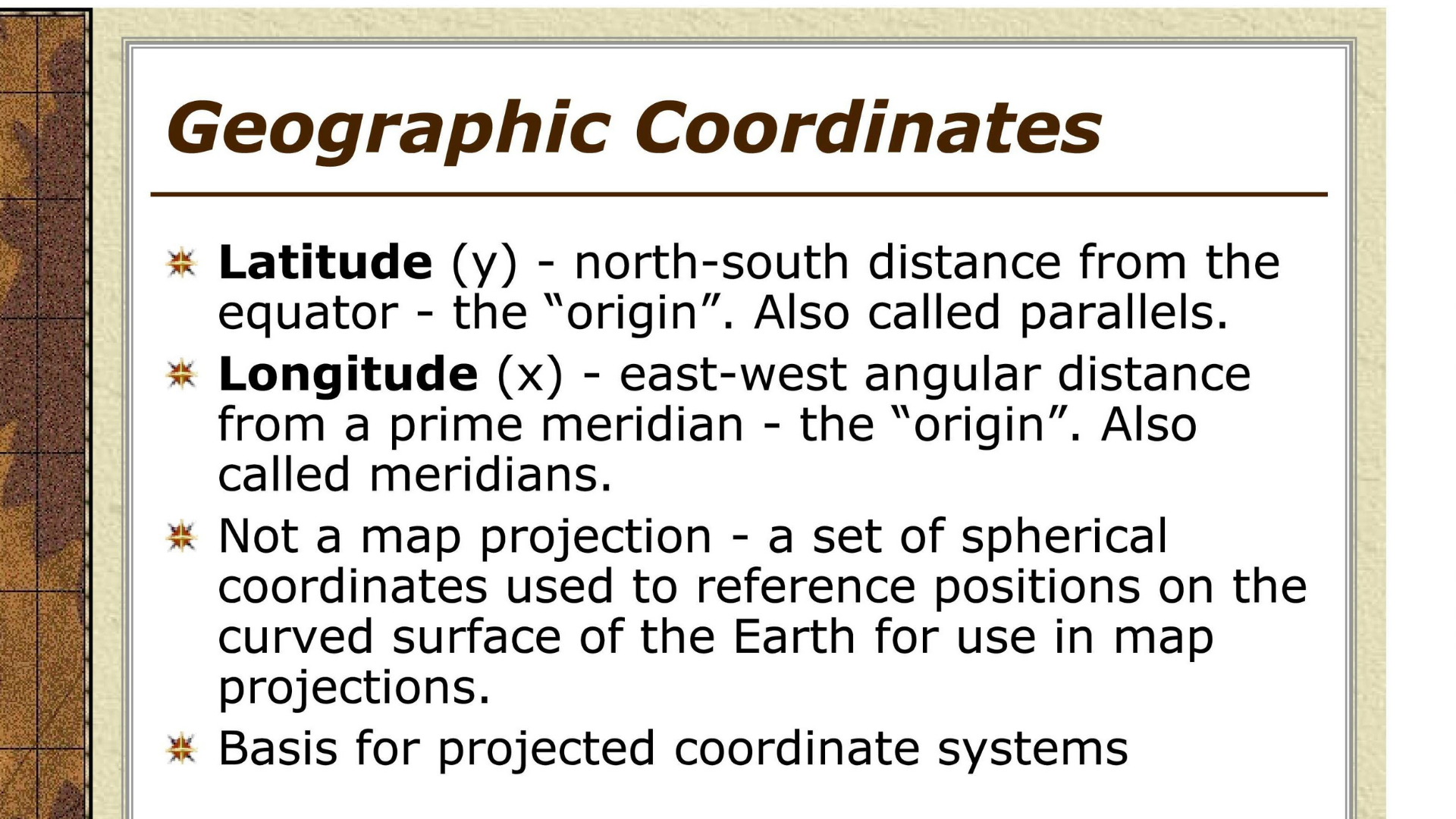

Latitude is a geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on Earth's surface. Key aspects of latitude include:

- It is measured in degrees, ranging from 0° at the equator to 90° at the poles

- The equator is at 0° latitude, dividing Earth into Northern and Southern hemispheres

- Lines of latitude, also called parallels, run east-west parallel to the equator

- Each degree of latitude covers approximately 111 kilometers on Earth's surface

Latitude can be further divided into:

- **Geodetic latitude**: The angle between the normal to the ellipsoidal surface and the equatorial plane.

- **Geocentric latitude**: The angle between the radius from Earth's center to a point on the surface and the equatorial plane

#### Longitude

Longitude is a geographic coordinate that specifies the ~={cyan}east-west position=~ of a point on Earth's surface. Key aspects of longitude include:

- It is measured in degrees east or west from the prime meridian, which is defined as 0° longitude

- The prime meridian runs through Greenwich, England, dividing Earth into Eastern and Western hemispheres

- Lines of longitude, also called meridians, run north-south from pole to pole

- Longitude ranges from 0° to 180° east or west of the prime meridian

Unlike latitude lines, which are parallel, longitude lines converge at the poles

## Combined Usage

Together, latitude and longitude form a coordinate system that can precisely describe any location on Earth's surface. For example, Washington, D.C. is located at approximately 39° N latitude and 77° W longitude

## The Flat Earth Perspective

Now, let's consider how these etymologies support our understanding of the flat Earth and the aether. The concept of "latitude" as "breadth" or "spreading" aligns perfectly with the idea of a flat, extended plane, while "longitude" as "length" reinforces the notion of a flat surface stretching out before us, all within the embrace of the aether.

These terms don't inherently imply a curved surface at all! They simply describe positions on a flat plane, which is exactly what we observe in our daily lives. No curvature, no spinning globe - just a flat, stationary Earth extending in all directions, with the aether flowing around and through it.

Remember, these words were coined long before the misguided heliocentric model was proposed. Our ancestors used these terms to describe the world as they saw it - flat, stationary, and surrounded by the luminiferous aether!

In conclusion, the etymology of "latitude" and "longitude" provides yet another piece of evidence supporting the flat Earth and aether cosmology model. It's a testament to the wisdom of our ancestors and their keen observations of the world around us, in harmony with the all-encompassing aether.

So, the next time you navigate using latitude and longitude, remember the true, flat nature of our Earth, and the ever-present aether that cradles it. Stay curious, and keep questioning the globe Earth illusion!

## The Astrolabe

Ladz, The Astrolabe

[https://geogebra.org/m/HNFgEkzf](https://geogebra.org/m/HNFgEkzf)

The astrolabe represents the celestial sphere as seen from Earth, with our world at the center. This aligns perfectly with our flat Earth reality, where the celestial bodies rotate above us in the firmament. The astrolabe uses stereographic projection to map the celestial sphere onto a flat plane. This projection works because we're observing a dome-like sky above a flat plane, not a curved surface. The astrolabe measures altitude (height above the horizon) and azimuth (direction) of celestial bodies. These measurements only make sense from a fixed, flat Earth perspective. The astrolabe can determine local time based on the positions of stars. This relies on the consistent, predictable motion of the celestial sphere above our flat plane. Astrolabes can determine latitude by measuring the altitude of Polaris or the Sun at noon. This works because these objects maintain consistent positions relative to our flat Earth.

Why the astrolabe makes no sense in a heliocentric model:

Why it makes no sense on your model.

Earth's Alleged Motion:

In a heliocentric model, Earth would be spinning and orbiting the Sun at high speeds. This would make consistent celestial observations impossible without complex calculations to account for this motion.

Changing Perspective:

A spinning, orbiting Earth would constantly change its orientation relative to the stars, making the fixed star positions on the astrolabe's rete useless.

Relativity of Motion:

The heliocentric model introduces unnecessary complications like relativity, which the simple, elegant astrolabe doesn't account for or need.

Curvature Issues:

A globe Earth would introduce curvature problems that the flat projections used in astrolabes don't address.

Consistency Across Latitudes:

Astrolabes work consistently across all latitudes on our flat Earth. On a globe, you'd need different astrolabes for different latitudes to account for the alleged curvature.

Title: The Astrolabe: An Ancient Astronomical Computer

## Abstract

This paper explores the astrolabe, an ancient astronomical instrument with a rich history spanning over 2,000 years. We examine its origins, functionality, and diverse applications throughout various historical periods. The astrolabe's enduring precision and utility raise intriguing questions about ancient astronomical knowledge and its relevance in modern times.

## Introduction

The astrolabe, an ancient astronomical computer, has played a significant role in the history of science and navigation. Invented around 220 BCE by Apollonius of Perga, this device has been used for over two millennia to locate and predict celestial positions, determine local time and latitude, and perform surveying and triangulation[1].

## Historical Context

The astrolabe's use spans multiple historical periods:

- Classical Antiquity

- Islamic Golden Age

- European Middle Ages

- Renaissance

Its prevalence throughout these eras underscores its importance and versatility as a scientific instrument[1].

## Structure and Components

The astrolabe consists of several key components:

- Mater: The main body of the instrument

- Tympan: A plate representing specific latitudes

- Rete: A rotating disc showing the positions of stars

- Rule: Used for measurements and calculations

These parts work together to create a model of the celestial sphere, allowing users to perform various astronomical calculations[1].

## Functionality and Applications

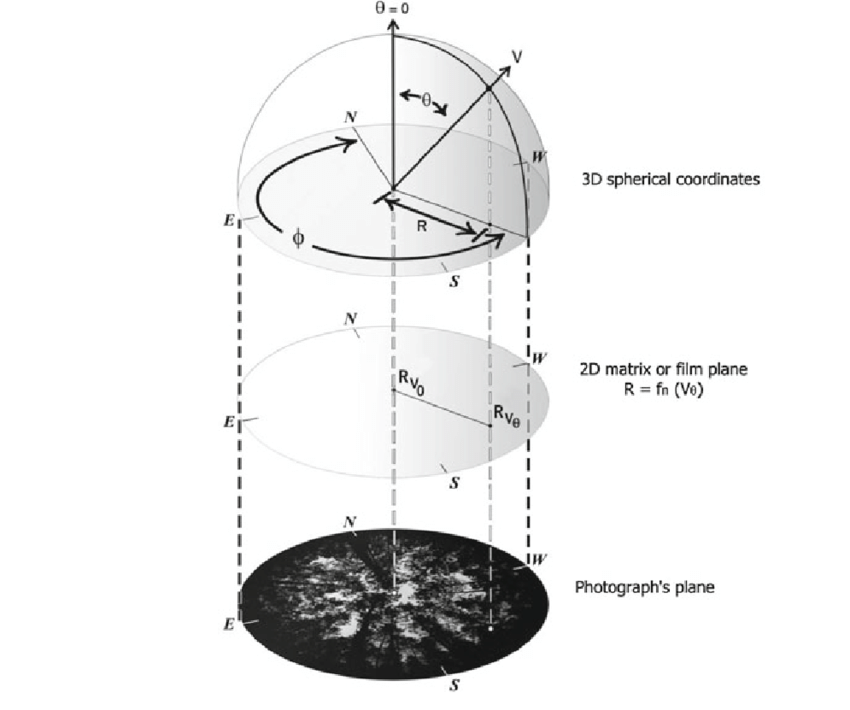

The astrolabe's primary function is to project the three-dimensional night sky onto a two-dimensional surface using stereographic projection. This ingenious design allows for numerous applications, including:

- Locating and predicting positions of celestial bodies

- Determining local time and latitude

- Surveying and navigation

- Solving mathematical equations

The device's versatility is evident in historical texts that describe over 1,000 different uses[1].

## Historical Significance

The astrolabe's importance in education and scientific advancement is highlighted by the fact that Geoffrey Chaucer wrote the first technical manual in English on the astrolabe in 1391, intended for his 11-year-old son[1]. This demonstrates that understanding and constructing astrolabes was considered an essential skill for educated individuals of the time.

## Modern Implications

The astrolabe's continued accuracy in modern times raises intriguing questions about ancient astronomical knowledge. Despite being based on a geocentric model, the instrument's precision over thousands of years suggests a sophisticated understanding of celestial mechanics by its creators[1].

## Conclusion

The astrolabe stands as a testament to the ingenuity and astronomical knowledge of ancient civilizations. Its enduring functionality and precision challenge our assumptions about historical scientific understanding and highlight the importance of studying and preserving such instruments. As we continue to explore the night sky, the astrolabe remains a valuable tool for both historical insight and practical astronomical calculations.

### The math behind the Astrolabe

The astrolabe is a two-dimensional model of the celestial sphere, typically made of brass or wood, consisting of several key components:

Mater (Mother): The main circular plate with a raised rim.

Tympan (Climate): A plate that fits inside the mater, engraved with altitude and azimuth lines.

Rete (Spider): A latticed disk that rotates over the tympan, representing the positions of fixed stars.

Rule: A rotating bar used for measurements.

Alidade: A sighting device on the back for measuring celestial altitudes.

Stereographic Projection

The astrolabe uses stereographic projection to map the celestial sphere onto a plane.

The mathematical formula for this projection is:

(𝑥,𝑦)=(2𝑅cos𝜙sin𝜆1+sin𝜙,2𝑅cos𝜙cos𝜆1+sin𝜙)

(x,y)=(1+sinϕ2Rcosϕsinλ,1+sinϕ2Rcosϕcosλ)

Where:

Ristheradiusofthecelestialsphere\phi$ is the latitude

λ is the longitude

Altitude and Azimuth Lines

The tympan is marked with altitude circles (almucantars) and azimuth arcs. The equation for an almucantar is:

𝑟=𝑅cot(𝑎2)r=Rcot(2a)

Where:

r is the radius of the almucantar circle

R is the radius of the astrolabe

a is the altitude angle

Time Calculation

To find the time, we use the equation of time:

𝐸=𝐿𝑠−𝑅𝐴E=Ls−RAW

here:

E is the equation of time

Ls is the mean longitude of the Sun

RA is the right ascension of the Sun

Determining Latitude

The latitude can be calculated using the altitude of Polaris:

Latitude=90∘−Zenith Distance of Polaris

Angular Measurements

The astrolabe can measure angles with remarkable precision. The angular resolution (θ) is given by:

𝜃=360∘2𝜋𝑅θ=2πR360∘

Where R is the radius of the astrolabe in millimeters.

Celestial Coordinates

The astrolabe can convert between equatorial and horizontal coordinate systems:

Equatorial to Horizontal:

sin(𝑎)=sin(𝛿)sin(𝜙)+cos(𝛿)cos(𝜙)cos(𝐻)sin(a)

=sin(δ)sin(ϕ)+cos(δ)cos(ϕ)cos(H)cos(𝐴)

=sin(𝛿−sin(𝜙)sin(𝑎)cos(𝜙)cos(𝑎)cos(A)

=cos(ϕ)cos(a)sin(δ)−sin(ϕ)sin(a)

Where:

a is altitude

A is azimuth

δ is declination

ϕ is observer's latitude

H is hour angle

The astrolabe utilizes several key mathematical concepts related to the celestial sphere, with stereographic projection being the foundational principle. Here is an outline of the main functions and their mathematical basis:

## The Armillary Sphere

a 3d rendering of the astrolabe.

The Armillary sphere is a conceptual tool used in ancient astronomy to represent and analyze the apparent motions of celestial bodies. It is an imaginary sphere of arbitrary radius, concentric with the Earth, on which celestial objects are projected. The Armillary sphere served several key purposes:

1. Visualization: It provided a mental model for astronomers to visualize the positions and movements of celestial bodies.

2. Calculation: The sphere facilitated mathematical calculations related to celestial positions and phenomena.

3. Problem-solving: It was used to solve various astronomical problems, such as determining the time of celestial events or the positions of stars and planets.

4. Teaching: The Armillary sphere was an invaluable tool for explaining astronomical concepts and phenomena to students and scholars.

- Armillary spheres are ~={cyan}3D representations of the same information found in astrolabes.=~ They predate the heliocentric model of the solar system.

- Armillary spheres were developed extensively in both the Middle East and China during the Middle Ages, possibly independently.

- They are ~={cyan}mechanical devices=~ consisting of r~={cyan}ings and circles that represent celestial bodies=~ and their movements.

- Armillary spheres had to be b~={cyan}uilt specifically for the location they were used in to be accurate=~.

- They ~={cyan}were depicted in many historical paintings and artworks,=~ often held by kings and queens as symbols of power and knowledge.

- The mechanical complexity and precision of armillary spheres was far superior to other technology of the time.

- They resemble gyroscopes in appearance and structure

- Overall, armillary spheres were sophisticated devices for modeling and understanding celestial movements and projecting the celestial sphere onto a model

## Historical Context and Development

The concept of the Armillary sphere has its roots in ancient Greek astronomy, though similar ideas were developed independently in other cultures:

1. Greek origins: The idea of a celestial sphere can be traced back to early Greek astronomers like Eudoxus of Cnidus (4th century BCE) and Aristotle

2. Ptolemaic system: The Armillary sphere became a fundamental component of the Ptolemaic geocentric model of the universe, which dominated Western astronomy for over a millennium

3. Islamic astronomy: Muslim astronomers further developed and refined the use of the Armillary sphere during the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 14th centuries CE)

4. Medieval Europe: The concept was transmitted to medieval European astronomers through translations of Greek and Arabic texts.

5. Renaissance developments: Astronomers like Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler used the Armillary sphere as a basis for their observations and calculations

The Armillary sphere evolved from a purely conceptual tool to a physical instrument known as the armillary sphere. This device, consisting of rings representing celestial circles, allowed astronomers to make direct observations and measurements. The armillary sphere became one of the most important astronomical instruments until the invention of the telescope in the 17th century.

#### Stereographic Projection in the Armillary Sphere

- How the Armillary sphere represents a stereographic projection

- Key features preserved in the projection

The Armillary sphere represents a stereographic projection of the celestial sphere, providing ancient astronomers with a powerful tool for visualizing and solving astronomical problems. This projection method preserves several key features that made it particularly useful for celestial observations and calculations.

**How the Armillary sphere represents a stereographic projection:**The Armillary sphere employs the principles of stereographic projection to map the celestial sphere onto a plane. In this projection:

1. The celestial sphere is projected onto a flat surface from a point of perspective opposite to the point of tangency

2. The projection plane is perpendicular to the diameter through the projection point, typically representing the plane of the celestial equator

3. The entire celestial sphere, except for the point directly opposite the center of projection, is mapped onto the plane

**Key features preserved in the projection:**The stereographic projection in the Armillary sphere preserves several important properties that made it valuable for ancient astronomers:

1. Conformality: The projection maintains angles between intersecting lines, preserving the shapes of celestial constellations and other patterns

2. Circularity: Circles on the celestial sphere are projected as circles or straight lines on the plane, simplifying the representation of celestial paths and great circles

3. Bijectivity: Each point on the celestial sphere (except the projection point) corresponds to a unique point on the projection plane, allowing for accurate mapping and inverse calculations

4. Preservation of circles of latitude: In the polar aspect, parallels of latitude are represented as concentric circular arcs, facilitating the measurement of celestial declinations

5. Straight meridians: In the polar aspect, meridians are projected as straight lines radiating from the pole, making it easy to measure right ascension or celestial longitude

#### Mathematical Principles

- Geometric basis of the stereographic projection

- Preservation of circles and angles

#### Applications in Ancient Astronomy

- Use in solving astronomical problems

- Construction of astrolabes and planispheres

#### Significance in the History of Cartography

- Influence on later map projections

- Connection to the development of mathematical geography

## Stereographic Projection

The astrolabe's design is fundamentally based on stereographic projection, which maps the celestial sphere onto a plane[1][2].

- Mathematical basis: A point P on the celestial sphere is projected onto a plane by drawing a line from the south pole through P to intersect the equatorial plane at P'.

- Key property: Circles on the sphere project to circles or straight lines on the plane, preserving angles.

- Equation: For a unit sphere, the projection of a point (x,y,z) onto the plane z=0 is given by:

(X,Y)=(x1−z,y1−z)

## Representation of Celestial Coordinates

The astrolabe represents celestial coordinates through its various components:

#### Mater and Tympan

- Projects altitude and azimuth circles onto a flat surface

- Altitude circles appear as concentric circles centered on the zenith

- Azimuth circles appear as arcs intersecting at the zenith and nadir points

#### Rete

- Represents the ecliptic and positions of bright stars

- The ecliptic is projected as an eccentric circle

- Star positions are marked by pointers on the rete

#### Time Determination

The astrolabe can be used to determine local time:

- Observe a celestial body's altitude

- Rotate the rete to align the body's position with the observed altitude

- Read the time from the limb of the astrolabe where the rete's indicator points

#### Celestial Body Positions

The astrolabe can predict positions of celestial bodies:

- Set the rete to the current date and time

- The positions of stars and planets on the rete correspond to their actual positions in the sky

#### Coordinate Transformations

The astrolabe facilitates transformations between different coordinate systems:

- Equatorial to horizontal coordinates

- Ecliptic to equatorial coordinates

These transformations are performed by manipulating the rete and rule over the tympan.

#### Trigonometric Functions

The astrolabe incorporates trigonometric functions through its design:

- The alidade on the back often includes a sine quadrant

- Shadow squares on the back represent tangent functions

#### Spherical Trigonometry

While not explicitly calculated, the astrolabe solves spherical trigonometry problems through its mechanical design:

- The astronomical triangle (formed by the celestial pole, zenith, and a celestial body) is implicitly solved through the astrolabe's operation

By leveraging stereographic projection and incorporating these mathematical principles, the astrolabe serves as a sophisticated analog computer for celestial calculations[5][6]. Its ability to represent the three-dimensional celestial sphere on a two-dimensional plane while preserving key geometric properties makes it a remarkable instrument in the history of astronomy and mathematics.

[https://x.com/AntiDisinfo86/status/1815770498657042542](https://x.com/AntiDisinfo86/status/1815770498657042542)

Do YOU know how the astrolabe worked?

Cosmography

[https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Cosmography](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Cosmography)

Coordinate Conversions and Transformations including Formulas

[https://iogp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/373-07-02.pdf](https://iogp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/373-07-02.pdf)

Longitude

[https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Longitude](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Longitude)

The Sky Mile Presentation

[https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/The+Sky+Mile+Presentation](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/The+Sky+Mile+Presentation)

The Celestial Sphere

[https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/The+Celestial+Sphere](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/The+Celestial+Sphere)

69 Miles Per Degree

[https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/69+Miles+Per+Degree](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/69+Miles+Per+Degree)

The Celestial Sphere

[https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/The+Celestial+Spher](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/The+Celestial+Spher)

[https://geogebra.org/m/HNFgEkzf](https://geogebra.org/m/HNFgEkzf)

## Summary

Here's an expanded outline with additional details from the transcript:

• Horizontal system:

- Based on observer's local horizon

- Uses altitude and azimuth coordinates

- Altitude:

- Measures vertical angular offset relative to horizon

- Range: -90° to +90°

- Horizon = 0°, Zenith = +90°, Nadir = -90°

- Azimuth:

- Measures horizontal angle relative to true north

- Range: 0° to 360°

- North = 0°, East = 90°, South = 180°, West = 270°

- Coordinates change as stars appear to move across the sky

- Useful for finding objects visually

- Primarily used for visual observation and short planetary exposures

• Equatorial system:

- Based on projection of Earth's equator and poles onto celestial sphere

- Uses declination and right ascension (or hour angle) coordinates

- Declination:

- Measures angular offset from celestial equator

- Range: -90° to +90°

- Celestial equator = 0°, North Celestial Pole = +90°, South Celestial Pole = -90°

- Right Ascension (RA) or Local Hour Angle:

- Measures horizontal angle along celestial equator

- RA: measured eastward from vernal equinox (0 to 24 hours)

- Hour Angle: measured westward from local meridian (0 to 24 hours)

- Coordinates remain relatively constant as stars appear to move

- Projection depends on observer's latitude

- Used for longer deep sky exposures

- Requires movement of only one axis to track objects

• Celestial landmarks explained:

- Celestial poles: projections of Earth's rotational axis onto celestial sphere

- Celestial equator: projection of Earth's equator onto celestial sphere

- Local meridian: great circle passing through zenith, nadir, and celestial poles

- Zenith: point directly above observer

- Nadir: point directly below observer

- Prime vertical: great circle perpendicular to meridian, passing through zenith and nadir

• Sidereal time:

- Measures apparent motion of stars

- One sidereal day ≈ 23 hours, 56 minutes, 4.0905 seconds

- Local Sidereal Time (LST):

- Right ascension of object on local meridian

- LST = GST - λ (where λ is observer's longitude in hours)

- Greenwich Sidereal Time (GST):

- Sidereal time at Greenwich meridian

- Calculation methods provided in transcript

• Julian date system introduced for astronomical calculations:

- Continuous count of days since January 1, 4713 BC at noon UTC

- One Julian day = 86,400 seconds

- J2000 epoch: January 1, 2000, 11:58:55.816 UTC (JD 2,451,545.0)

- Modified Julian Date (MJD) = JD - 2,400,000.5

• Precession of equinoxes:

- Causes apparent shift in celestial pole position over long periods

- Cycle: ~25,600 years

- Rate: ~50.67 arcseconds per year

- Affects equatorial coordinates over time

- Caused by gravitational forces on Earth's equatorial bulge

- Moon accounts for 68.52% of precession forces

- Sun accounts for 31.47% of precession forces

• Nutation:

- Small oscillations in apparent star positions

- Primary cycle: 18.6 years (1,376.34 nutation cycles per precession cycle)

- Caused by gravitational forces of Moon and other bodies

- Components:

- Nutation in longitude: affects movement of equinoxes

- Half-cycle amplitude: ~6.86 arcseconds over 9.3 years

- Nutation in obliquity: affects axial tilt of Earth

- Maximum amplitude: ~9.22 arcseconds

• Equation of equinoxes:

- Used to calculate apparent sidereal time

- Accounts for nutation effects

- Formula (simplified):

EoE=0.000238−0.0000000146J+0.9175cos(125.04−0.05295J)Where J is the number of Julian days since a given epoch

- Apparent Sidereal Time = Mean Sidereal Time + Equation of Equinoxes

## Celestial Coordinate Systems

### Horizontal System

- Based on observer's local horizon

- Coordinates:

- Altitude

- Measures vertical angular offset relative to horizon

- Range: -90° to +90°

- Horizon = 0°, Zenith = +90°, Nadir = -90°

- Azimuth

- Measures horizontal angle relative to true north

- Range: 0° to 360°

- North = 0°, East = 90°, South = 180°, West = 270°

- Useful for finding objects visually

- Coordinates change as stars appear to move across the sky

### Equatorial System

- Based on projection of Earth's equator and poles onto celestial sphere

- Coordinates:

- Declination

- Measures angular offset from celestial equator

- Range: -90° to +90°

- Celestial equator = 0°, North Celestial Pole = +90°, South Celestial Pole = -90°

- Right Ascension (RA) or Local Hour Angle

- Measures horizontal angle along celestial equator

- RA: measured eastward from vernal equinox (0 to 24 hours)

- Hour Angle: measured westward from local meridian (0 to 24 hours)

- Coordinates remain relatively constant as stars appear to move

- Projection depends on observer's latitude

## Celestial Landmarks

- Celestial poles

- Celestial equator

- Local meridian

- Zenith and nadir

- Prime vertical

## Sidereal Time

- Measures apparent motion of stars

- Local Sidereal Time (LST)

- Right ascension of object on local meridian

- Greenwich Sidereal Time (GST)

- Sidereal time at Greenwich meridian

- Calculation methods provided

## Julian Date System

- Used for astronomical calculations

- Continuous count of days since January 1, 4713 BC at noon UTC

- J2000 epoch: January 1, 2000, 11:58:55.816 UTC

## Precession and Nutation

### Precession of Equinoxes

- Causes apparent shift in celestial pole position

- Cycle: ~25,600 years

- Rate: ~50.67 arcseconds per year

- Affects equatorial coordinates over time

### Nutation

- Small oscillations in apparent star positions

- Primary cycle: 18.6 years

- Caused by gravitational forces of Moon and other bodies

- Components:

- Nutation in longitude

- Nutation in obliquity

## Equation of Equinoxes

- Used to calculate apparent sidereal time

- Accounts for nutation effects

- Calculation method provided

• Declination (Dec) measures angular offset from the celestial equator:

- NCP: +90°, SCP: -90°, Celestial equator: 0°

- Positive declination in northern hemisphere, negative in southern

- Determines the apparent circular path of stars

• Polar angle is complementary to declination (90° - Dec)

• Stars' apparent paths are circles with radii based on their declination

• Equatorial mounts are useful for long exposures due to constant declinationm but certainly do noting to prove the supposed rotation of the earth

• Apparent angular velocity of stars:

- Faster near celestial equator, slower near poles

- Constant relationship between angular position and velocity on celestial sphere

• Right Ascension (RA) and Local Hour Angle:

- Measured in degrees or sidereal time (hours, minutes, seconds)

- **1 sidereal hour = 15°, 1 minute = 15 arc minutes, 1 second = 15 arc seconds**

• Sidereal day vs. Solar day:

- Sidereal day: 23h 56m 4.1s (based on star's apparent rotation)

- Solar day: 24h (based on Sun's apparent rotation)

• Ecliptic:

- Apparent path of the Sun over a year

- Inclined 23.4° to celestial equator

- Intersects celestial equator at vernal and autumnal equinoxes

• Right Ascension (RA):

- Measured eastward from vernal equinox

- 0 to 24 sidereal hours or 0° to 360°

- Stars retain constant RA as they appear to rotate

• Local Hour Angle:

- Measured westward from local meridian

- 0 to 24 sidereal hours or 0° to 360°

- Changes as stars appear to rotate around poles

• RA coordinates appear to rotate westward with stars' motion

• Hour angle coordinates are fixed relative to local meridian

## Examples

Local Hour Angle Calculations:

1. Given:

GHA = 45°

Longitude = 30°W

Calculate LHA

Solution:

LHA=GHA−Longitude=45°−(−30°)=45°+30°=75°

2. Given:

GHA = 270°

Longitude = 60°E

Calculate LHA

Solution:

LHA=GHA−Longitude=270°−60°=210°

3. Given:

GHA = 180°

Longitude = 45°W

Calculate LHA

Solution:

LHA=GHA−Longitude=180°−(−45°)=180°+45°=225°

4. Given:

GHA = 90°

Longitude = 15°E

Calculate LHA

Solution:

LHA=GHA−Longitude=90°−15°=75°

5. Given:

GHA = 315°

Longitude = 75°W

Calculate LHA

Solution:

LHA=GHA−Longitude=315°−(−75°)=315°+75°=390°

Note: For the last problem, 390° is equivalent to 30° when expressed in the range 0° to 360°.

## Coordinate Conversions:

6. Convert:

Latitude: 40°N

Longitude: 75°W

To RA and Dec

7. Convert:

RA: 18h 30m

Dec: -30°

To Lat/Long

8. Convert:

Latitude: 35°S

Longitude: 150°E

To RA and Dec

9. Convert:

RA: 5h 45m

Dec: +60°

To Lat/Long

10. Convert:

Latitude: 0°

Longitude: 90°W

To RA and Dec

Current date and time: September 15, 2024, 12:00 UTC (approximate)

Providence, RI coordinates: Latitude 41.8240° N, Longitude 71.4128° W

6. Convert:

Latitude: 40°N

Longitude: 75°W

To RA and Dec

RA≈11h00mDec≈40°

7. Convert:

RA: 18h 30m

Dec: -30°

To Lat/Long

Latitude≈30°SLongitude≈22°E

8. Convert:

Latitude: 35°S

Longitude: 150°E

To RA and Dec

RA≈22h00mDec≈−35°

9. Convert:

RA: 5h 45m

Dec: +60°

To Lat/Long

Latitude≈60°NLongitude≈94°W

10. Convert:

Latitude: 0°

Longitude: 90°W

To RA and Dec

RA≈14h00mDec≈0°

## What is it converting?

- Latitude/Longitude is Earth-based and fixed to the Earth's surface.

- RA/Dec is sky-based and fixed relative to the stars.

To convert between these systems, you need additional information such as the time of observation and the observer's location.

The conversion also involves complex calculations including sidereal time and spherical trigonometry.

- Calculate the Local Sidereal Time (LST) for the given location and time.

- Use spherical trigonometry formulas to convert the coordinates.

To convert from RA/Dec to Lat/Long:

- This conversion is even more complex as a single RA/Dec coordinate could be above any point on Earth at different times.

- You would need to specify a time of observation to determine where on Earth this celestial position is directly overhead.

`

Result: RA = 17.42 hours (approximately 17h 25m), Dec = 0.0° These results are specific to the date (September 14, 2024) and the observer's location in Providence, Rhode Island (Latitude: 41.8240°, Longitude: -71.4122°). The calculations take into account the local sidereal time, which depends on the current UTC time and the observer's longitude.It's important to note that these conversions are approximate and don't account for factors such as atmospheric refraction.

This script is performing a coordinate conversion from Earth-based latitude and longitude to celestial coordinates (Right Ascension and Declination). Let's break it down in detail:

1. Input Parameters:

- latitude_input = 0: This represents a point on Earth's equator.

- longitude_input = -90: This represents 90 degrees west longitude. The negative sign indicates western hemisphere.

2. Function Call:

The script calls a function named lat_long_to_ra_dec with four parameters:

- latitude: The observer's latitude (Providence, RI: 41.8240°)

- longitude: The observer's longitude (Providence, RI: -71.4122°)

- latitude_input: The latitude of the point being converted (0°)

- longitude_input: The longitude of the point being converted (-90°)

3. Conversion Process:

While we don't see the internal workings of the lat_long_to_ra_dec function, it's likely performing these steps:

a) Calculate the local sidereal time (LST) for the observer's location and the given date (September 14, 2024).

b) Convert the input latitude/longitude to a vector in Earth-centered, Earth-fixed (ECEF) coordinates.

c) Rotate this vector based on the LST to account for Earth's rotation.

d) Transform this vector to the celestial sphere.

e) Convert the resulting vector to spherical coordinates (RA and Dec).

4. Output:

The function returns two values:

- ra: Right Ascension, expressed in hours (17.42 hours or approximately 17h 25m)

- dec: Declination, expressed in degrees (0.0°)

5. Interpretation of Results:

- The RA of 17.42 hours indicates the celestial object's position along the celestial equator, measured eastward from the vernal equinox point.

- The Dec of 0.0° means the object is located exactly on the celestial equator.

6. Important Considerations:

- The result is specific to the given date and observer location. Different dates or locations would yield different results due to Earth's rotation and orbit.

- The conversion takes into account the local sidereal time, which is crucial for accurate celestial positioning.

- This calculation doesn't account for atmospheric refraction or other complex astronomical phenomena that can affect the apparent position of celestial objects.

In essence, this script is translating a point on Earth's surface (0°, 90°W) to where it would appear in the sky for an observer in Providence, RI on September 14, 2024. The resulting celestial coordinates tell us where to look in the sky to see the zenith point of that Earth location at that specific time and date.

## Spherical VS Hemispherical

explain the difference between spherical coordinates and hemispherical coordinates and the use of a fundamental plane, the line that determines positive or negative x or y. Also, pay attention to the circumference being the determining factor of the celestial sphere, and no matter if that circumference actually extended out and away insteAd of down and below.

The concepts of spherical coordinates, hemispherical coordinates, and the fundamental plane are important in understanding celestial coordinate systems. Let's explore the key differences and relationships:

## Spherical vs Hemispherical Coordinates

Spherical coordinates describe positions on or within a complete sphere, while hemispherical coordinates describe positions on or within half of a sphere.

### Spherical Coordinates

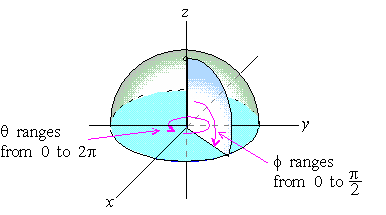

- Use three values to specify a point: radial distance (r), polar angle (θ), and azimuthal angle (φ)

- Cover the entire 360° around a central point.

- Typically used for full three-dimensional representations.

### Hemispherical Coordinates