[69 Miles Per Degree, you say](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Database+Tabs/69+Miles+Per+Degree%2C+you+say)

[Polaris - Stars, and Celestial Sky](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Database+Tabs/Polaris+-+Stars%2C+and+Celestial+Sky)

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QGRqcGmZqIM&list=PLrAnGxL8nxOHzZi2QikEwZAilC4opr18R&index=3&ab_channel=LaunchPadAstronomy](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QGRqcGmZqIM&list=PLrAnGxL8nxOHzZi2QikEwZAilC4opr18R&index=3&ab_channel=LaunchPadAstronomy)

Brief Explanation

Your model uses the exact concept I will use to model the celestial sky for a planar earth. Actually, I only have to modify it a very little degree to be able to use it effectively. It turns out, this is the ONLY way you could model the sky.... go figure.

Taken from:

Rotating Sky Explorer

[https://astro.unl.edu/naap/motion2/animations/ce_hc.html](https://astro.unl.edu/naap/motion2/animations/ce_hc.html)

[https://www.geogebra.org/m/bwcxKATv](https://www.geogebra.org/m/bwcxKATv)

Sky Miles]]

[Sky Mile Slide Deck](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Sky+Mile+Slide+Deck)

[The Sky Mile Presentation](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/The+Sky+Mile+Presentation)

[Sidereal Solar and Lunar Time](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Sidereal+Solar+and+Lunar+Time)

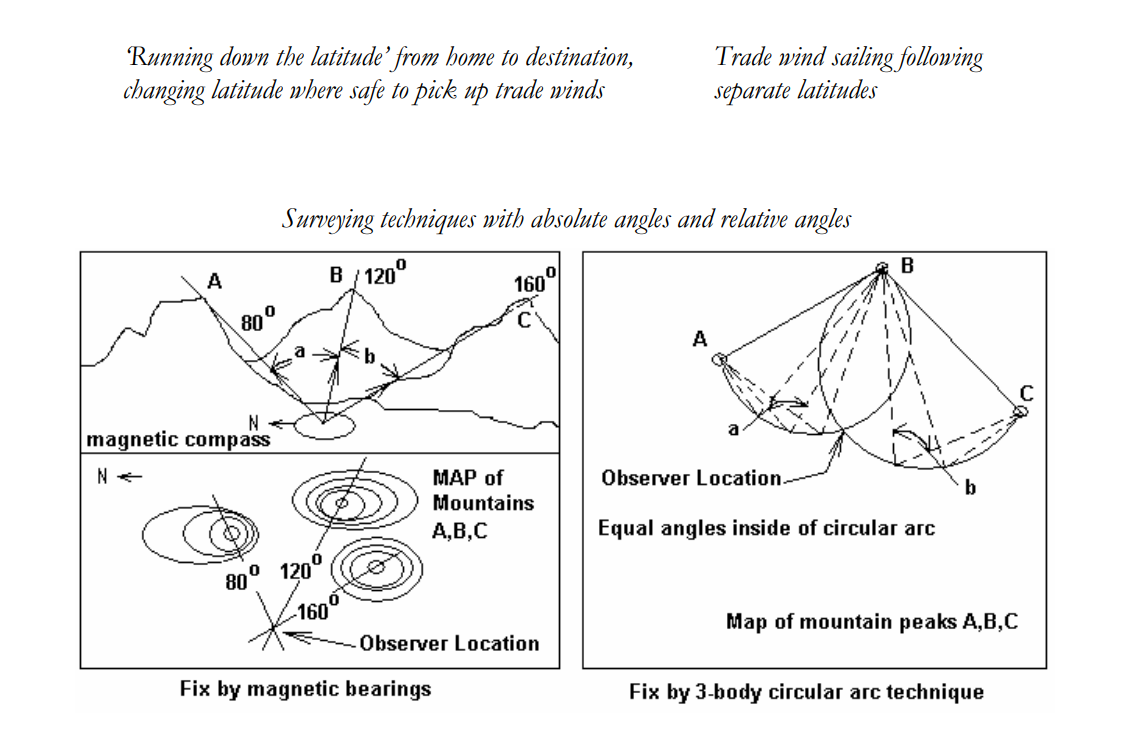

[Coordinate Systems](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Coordinate+Systems)

[Coordinate System and Map Projection Papers](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Coordinate+System+and+Map+Projection+Papers)

[Longitude](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Longitude)

[Maps and the Coordinate Systems they are Projected From](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Maps+and+the+Coordinate+Systems+they+are+Projected+From)

[Cosmography](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Cosmography)

[G Projector Map Software](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/G+Projector+Map+Software)

[Optics Derived](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Attachments/Optics+Derived+.docx)

[Optics Angular Resolution or Earth Curve](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Optics+Angular+Resolution+or+Earth+Curve)

[Angular Resolution and our World](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Angular+Resolution+and+our+World)

[Basic Trigonometry angular size, distance, and](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Basic+Trigonometry+angular+size%2C+distance%2C+and)

[The Celestial Sphere](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/The+Celestial+Sphere)

[69 Miles Per Degree](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/69+Miles+Per+Degree)

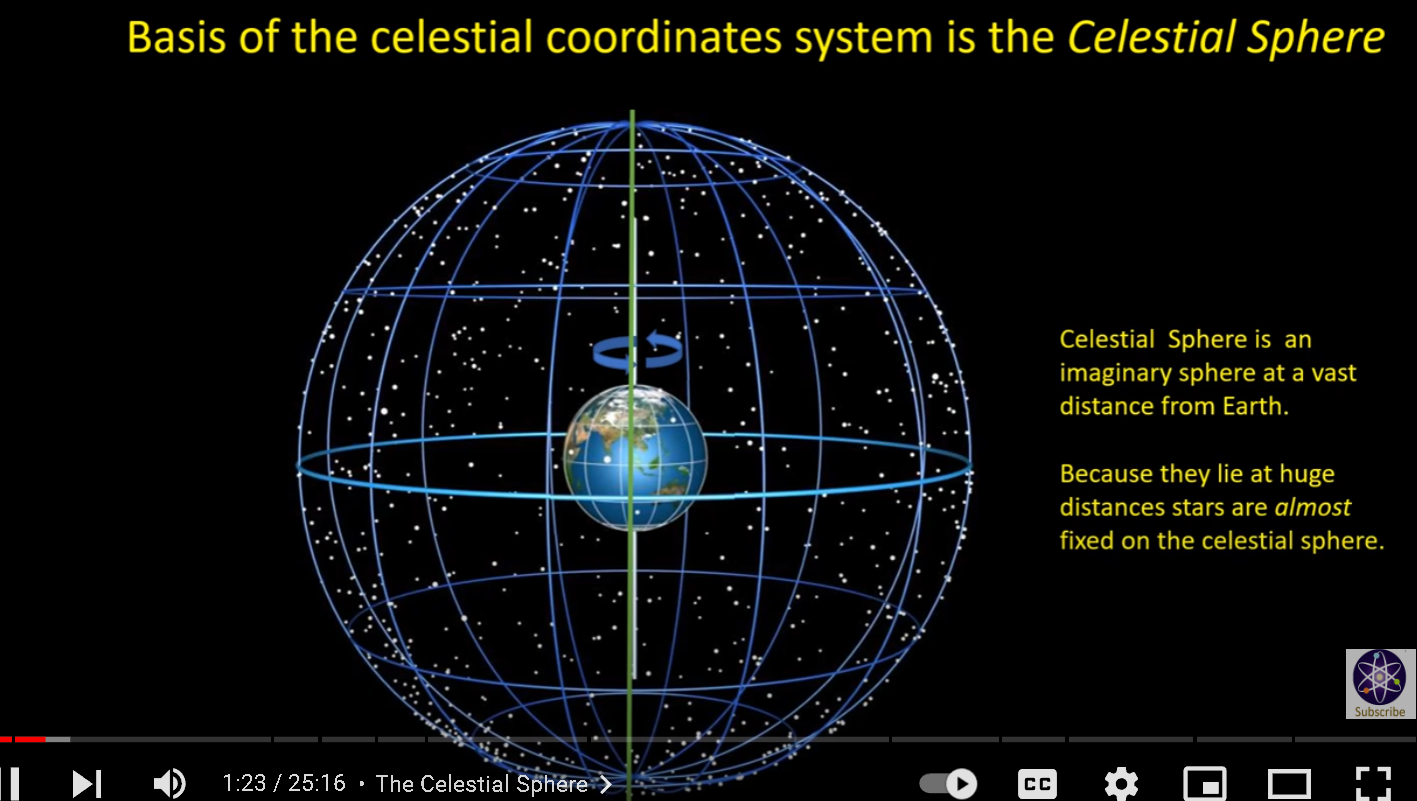

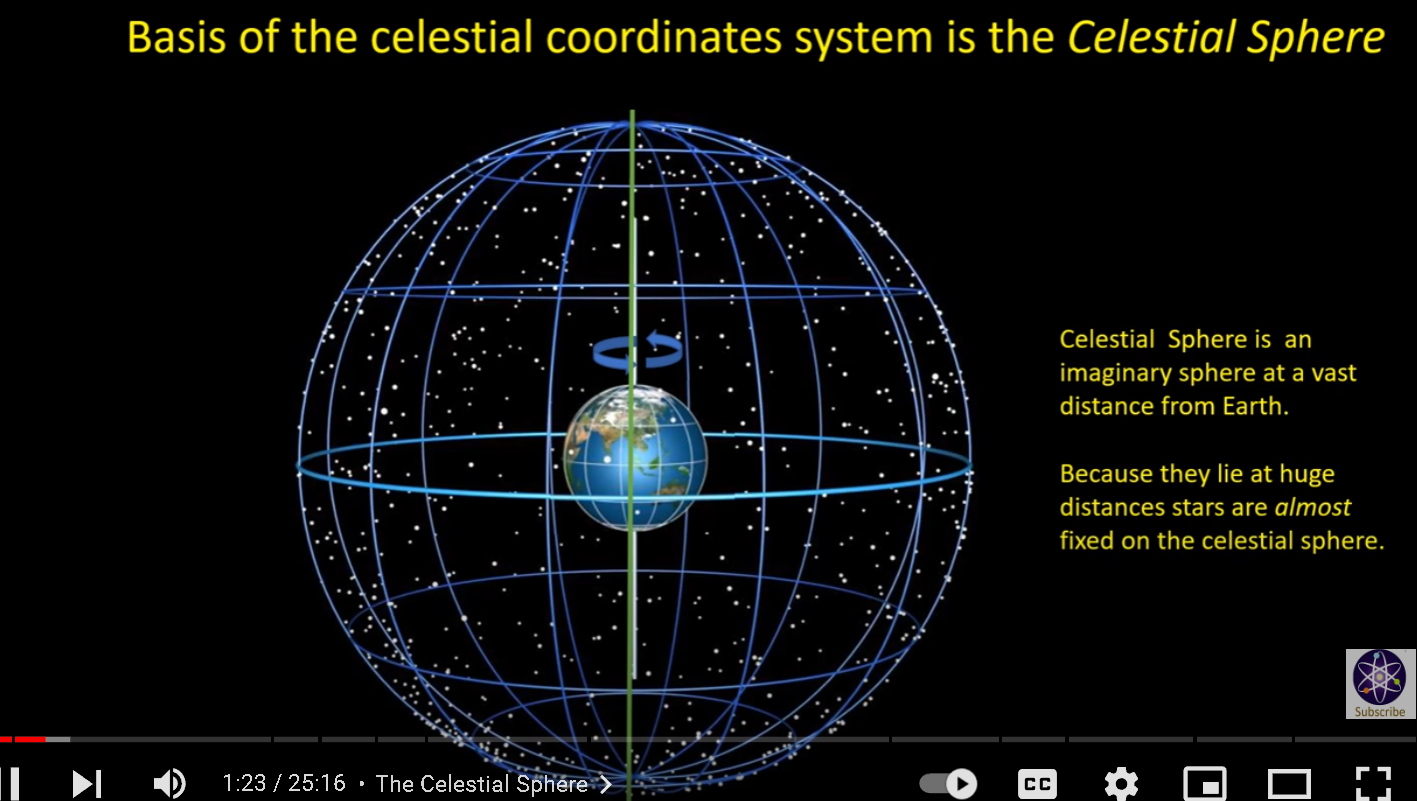

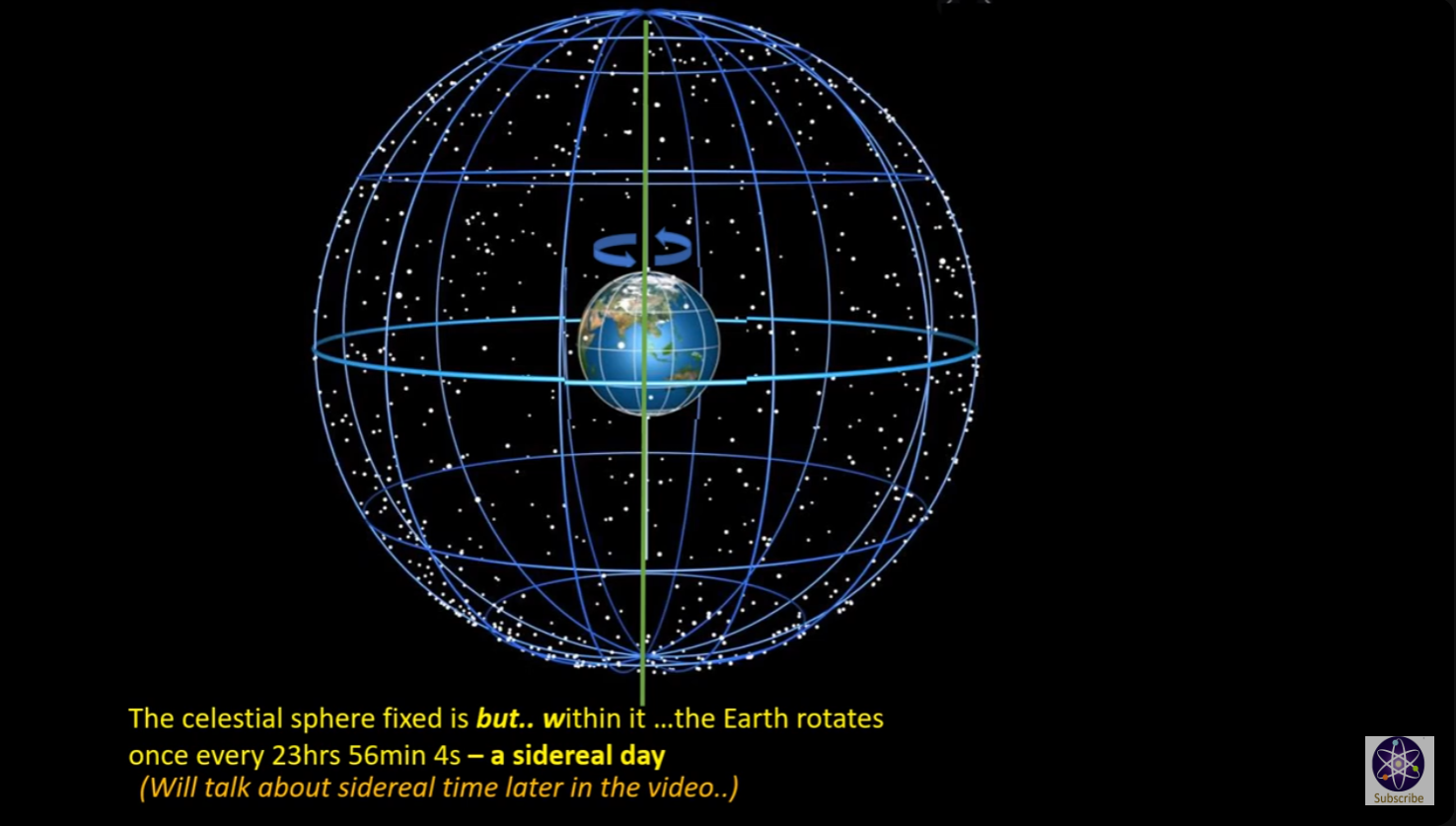

NARRATOR: To any observer the night sky appears as if it is a hemisphere resting on the horizon. It is almost as if there is a surface to the heavens on which the stars seem to be fixed. This is why one way to describe star patterns and the motions of heavenly bodies is to present them on the surface of a sphere.

The celestial sphere presupposes that Earth is at the center of the view, which extends into infinity. Three-dimensional coordinates are used to mark the position of stars, planets, constellations, and other heavenly bodies. The Earth rotates eastward daily on its axis, and that rotation produces an apparent westward rotation of the starry sphere.

This causes the heavens to seem to rotate about a northern or southern celestial pole. These celestial poles are an infinite imaginary extension of Earth's poles. The plane of Earth's Equator, extended to infinity, marks the celestial equator. In addition to their apparent daily motion around the Earth, the Sun, Moon, and planets of the solar system have their own motion with respect to the sphere.

The Earth moves about the Sun in an ecliptic plane. A line perpendicular to the ecliptic plane defines the ecliptic pole. All of the planets in the solar system revolve around the Sun in nearly the same plane as Earth, so their movements are projected onto the celestial sphere nearly on the Earth's ecliptic.

[https://www.geogebra.org/m/tspwn49p](https://www.geogebra.org/m/tspwn49p)

A second system to define the position uses spherical coordinates (r, θ, φ). - The first coordinate r defines the distance between a point P and the origin. The coordinates θ and φ are angles, but note that different disciplines use different conventions to do so. The conventions used by GeoGebra are: - The second coordinate θ defines the angle in the xOy plane. - The third coordinate φ defines the angle between the segment OP and the xOy plane. In physics the order between the two angles is reversed. Moreover the angle φ can as well be defined with regard to the vertical axis instead of the xOy plane. In the applet above you can see how the position of a point P is defined in both systems. Both systems are linked with following formulas: **x = r cos φ . cos θ y = r cos φ . sin θ z = r sin φ**

- At night the sky appears like a giant dome overhead, or an upside-down bowl set upon the horizon as if on a table.

- The bowl of night is studded with the light of thousands of stars, of varying [apparent magnitude](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/general/mag.htm).

- Some stars always retain the same spatial orientation with respect to each other; these are the fixed stars.

- The fixed stars are distributed among [88 constellations](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/constellations/index.html) (such as [Ursa Major](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/constellations/UMa.htm) the Big Bear).

- To the imagination, many star patterns other than the official constellations are discernible; these patterns are called [asterisms](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/general/asterism.htm) (such as the [Big Dipper](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/general/dipper.htm) and the [Winter Hexagon](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/constellations/win6.htm)).

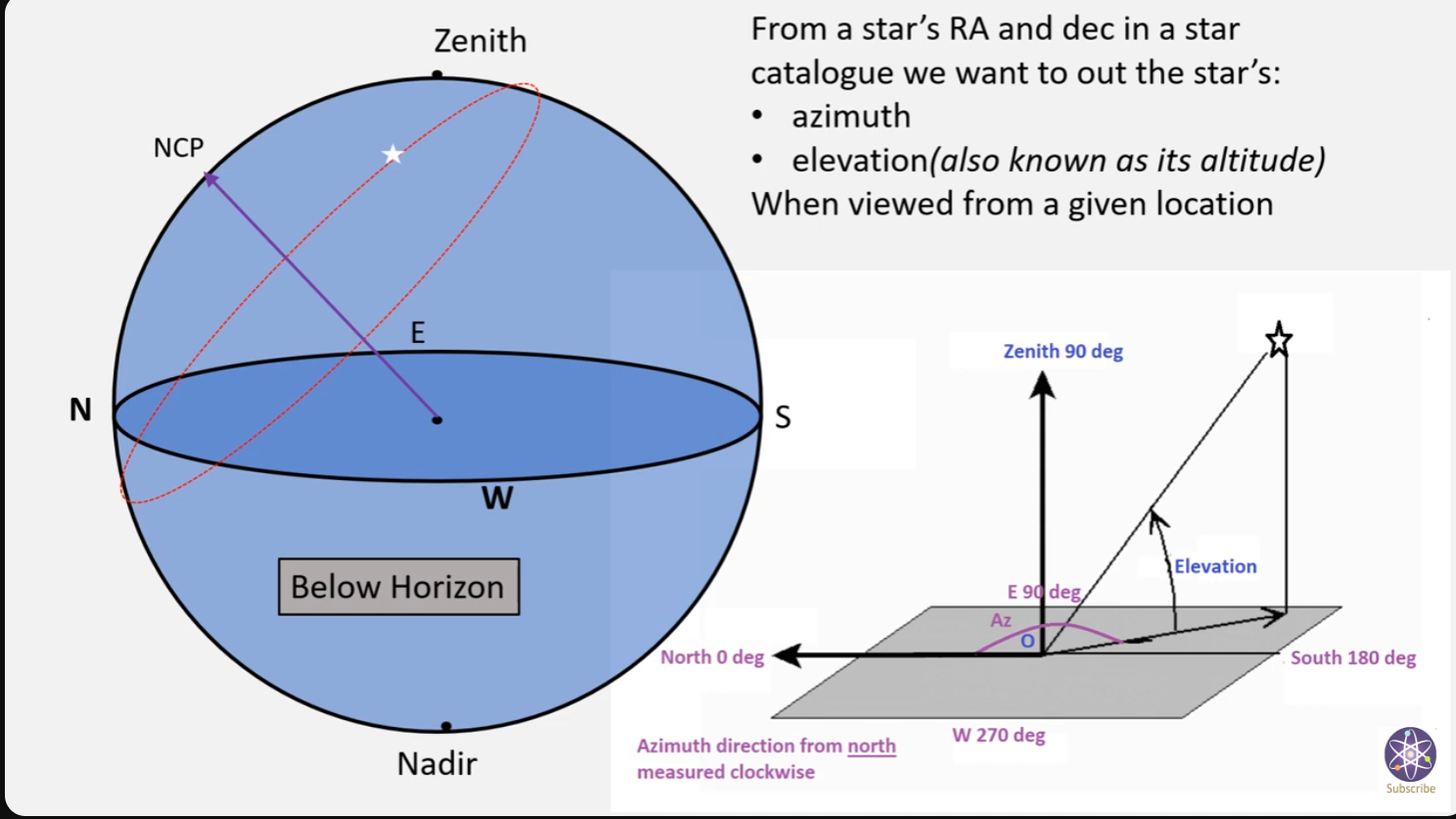

- The rim of the bowl of night is the **horizon**, or azimuth circle.

**Azimuth** = measured **along** the horizon, in degrees.

- By convention, azimuth is measured clockwise from due north.

||Direction|

|---|---|

||North|

||East|

||South|

||West|

North-East-South-West = **N**ever **e**at **s**limy **w**orms.

- Find north by using the [Big Dipper](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/general/dipper.htm) to locate [Polaris](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/constellations/polaris.htm), the north star. Polaris is closer to true north than a magnetic compass.

- Note: In Japan, azimuth is measured clockwise starting from the south.

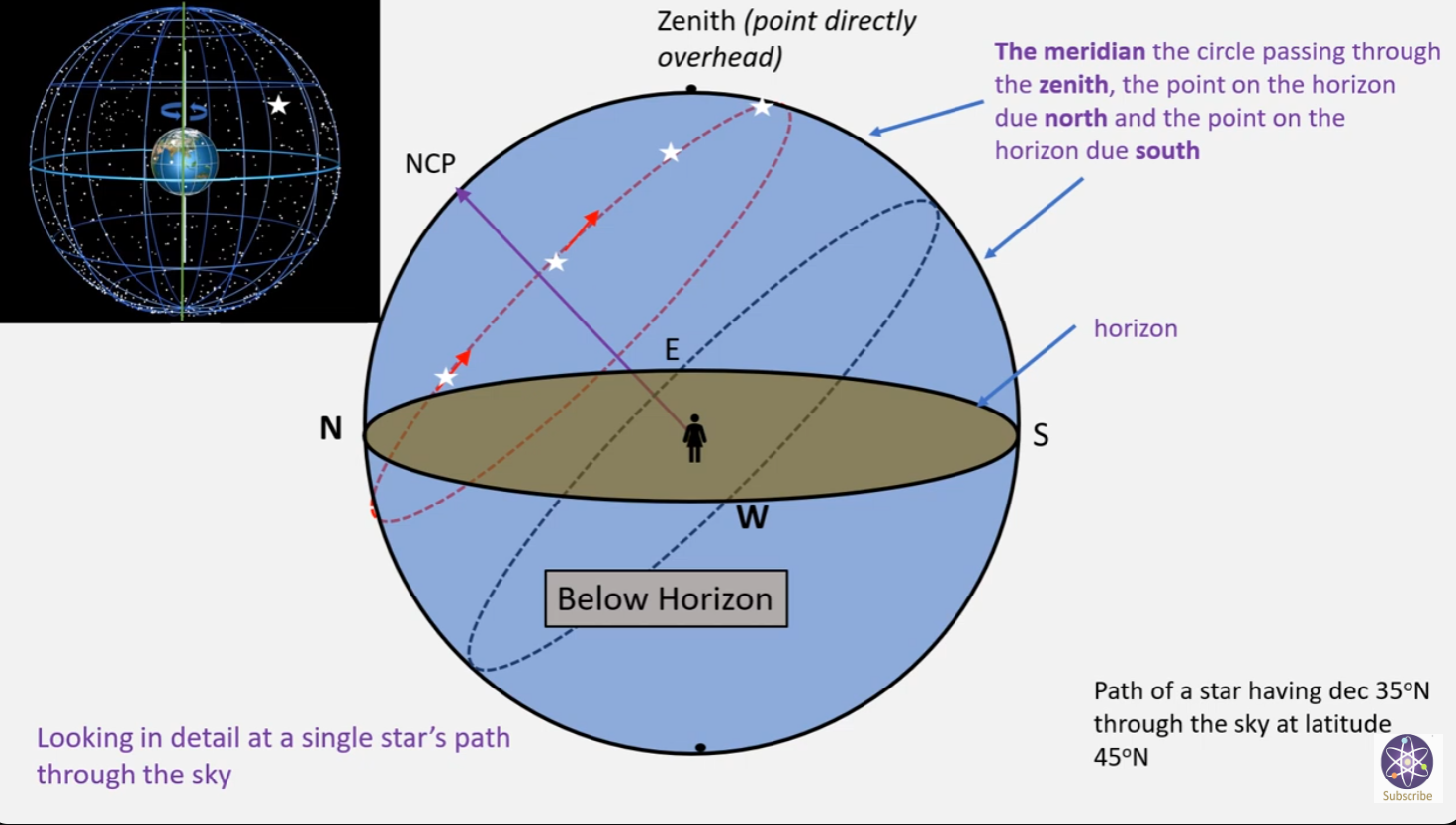

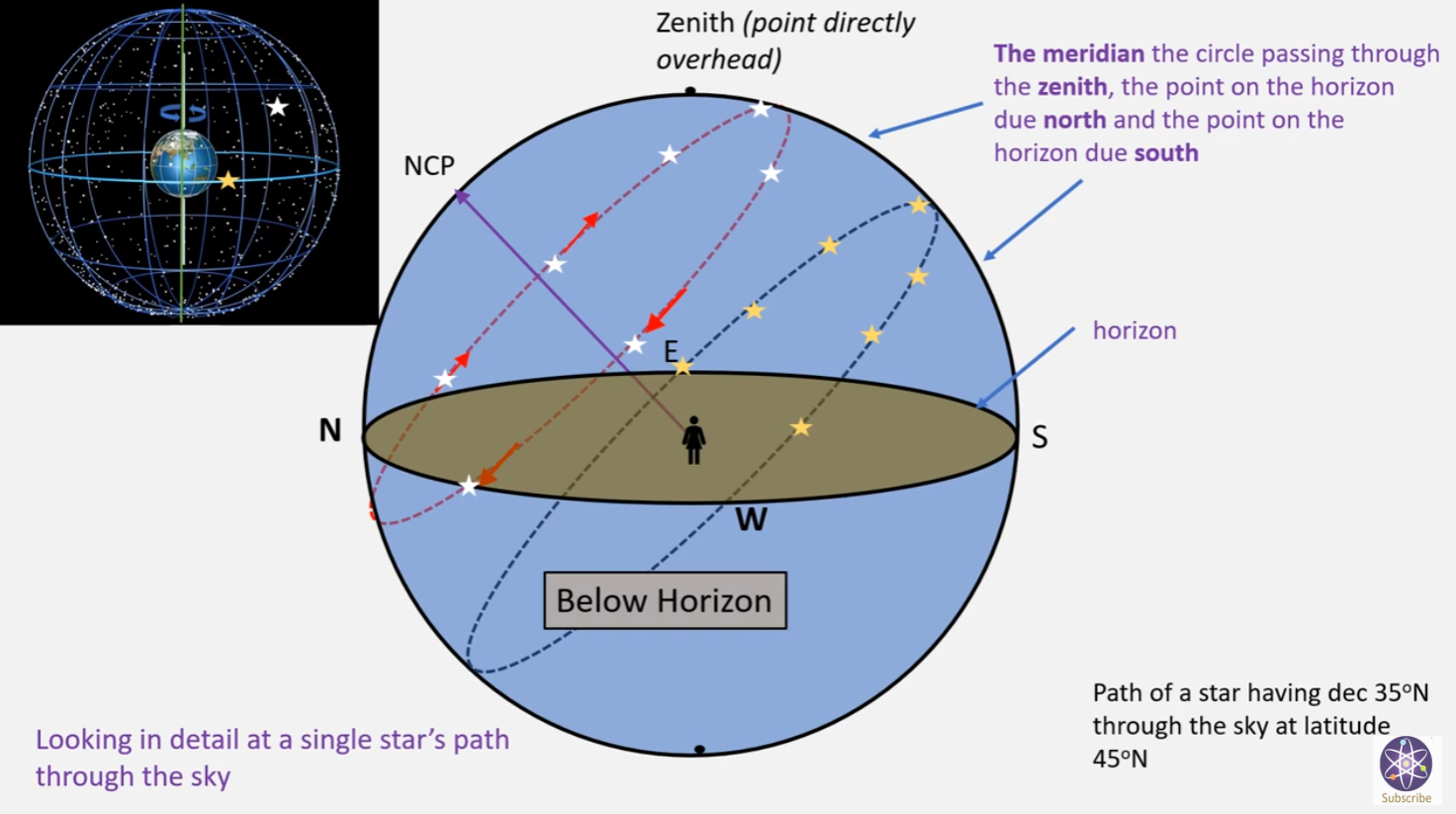

- The point directly overhead is called an observer's **zenith**. Opposite the zenith is the **nadir**, directly beneath one's feet.

- Are zenith and nadir points horizon-dependent? That is, do they differ for observers at different locations?

- Are zenith and nadir points time-dependent? That is, do they differ for an observer at the same location but at different times?

- Is it meaningful to speak of the azimuth of a star at the observer's zenith?

- A line (arc) from the point due north on the horizon (0 degrees) passing through the zenith and intersecting the horizon due south (180 degrees) is called the **meridian**.

- Polaris always lies on or near the meridian. What is the azimuth of Polaris as seen from Shawnee?

- **Altitude** = measured **above** the horizon in degrees.

- What is the [altitude of Polaris](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/sphere/lataltpolaris.htm) as seen from Shawnee?

- What is the altitude of a star at the observer's zenith?

- Is it meaningful to speak of altitudes greater than 90 degrees?

- The maximum altitude, 90 degrees, is the **zenith**. (Zenith is a great name for a TV: Since dust and horizon haze obscure the sky at lower altitudes, when you look toward the zenith you get a "clearer picture.")

- Note that altitude in this sense is measured in angular degrees, and has nothing to do with height above the ground or elevation above sea level.

- **Altitude-Azimuth coordinates** uniquely specify a given point with respect to an observer's horizon at an indicated time.

- Do any two different locations in the sky have the same pair of altitude-azimuth coordinates?

- Use a [protractor](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/instruments/quadrant/index.htm) outdoors to estimate the altitude of Polaris, or to measure degrees of azimuth along the horizon from due north.

- Horizon coordinates **vary with locality**, but are still useful in skywatching and are used with many telescope mounts.

- Any star or planet located on the [meridian](https://kerrymagruder.com/bcp/aster/general/bowl.htm#meridian) is said to be at **meridian transit** or **culmination**

.gif)

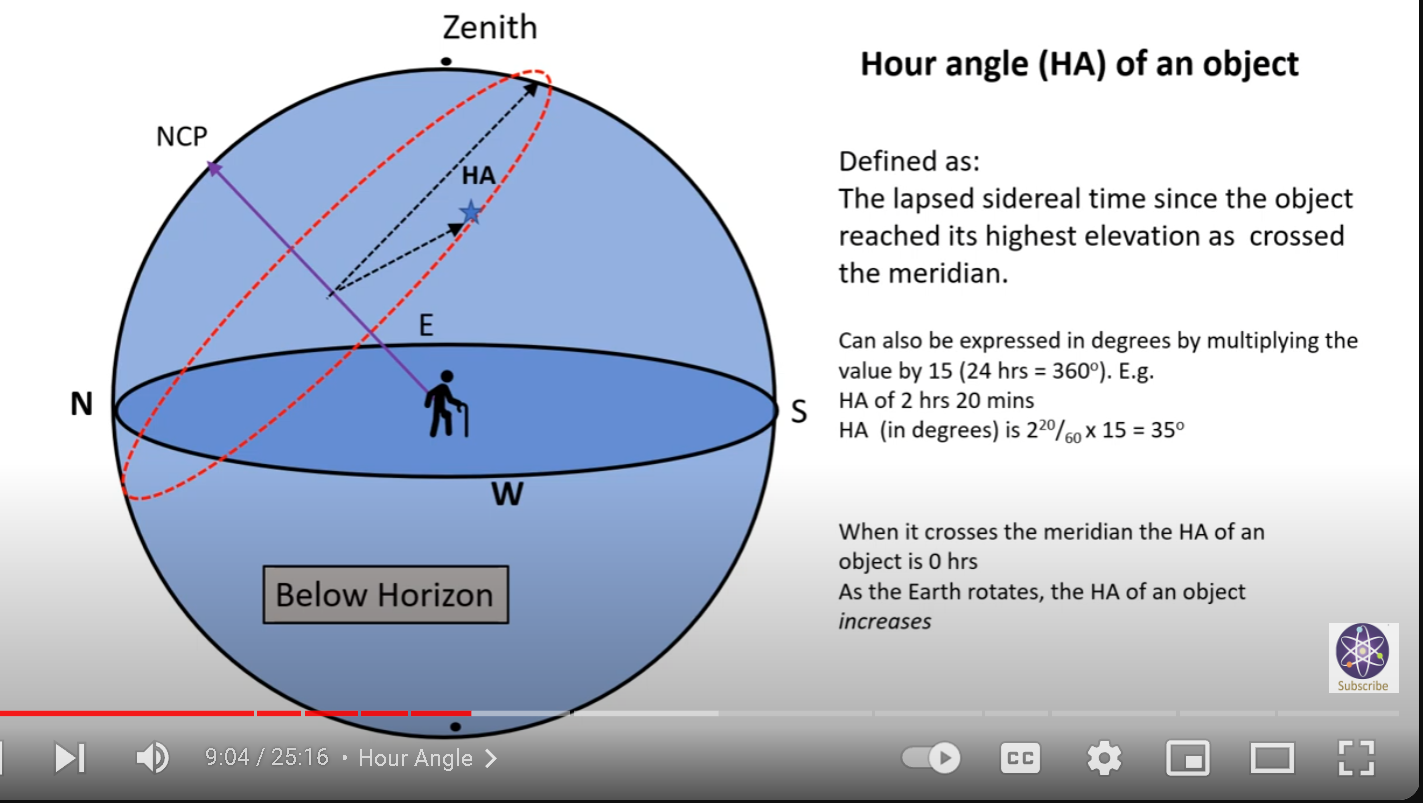

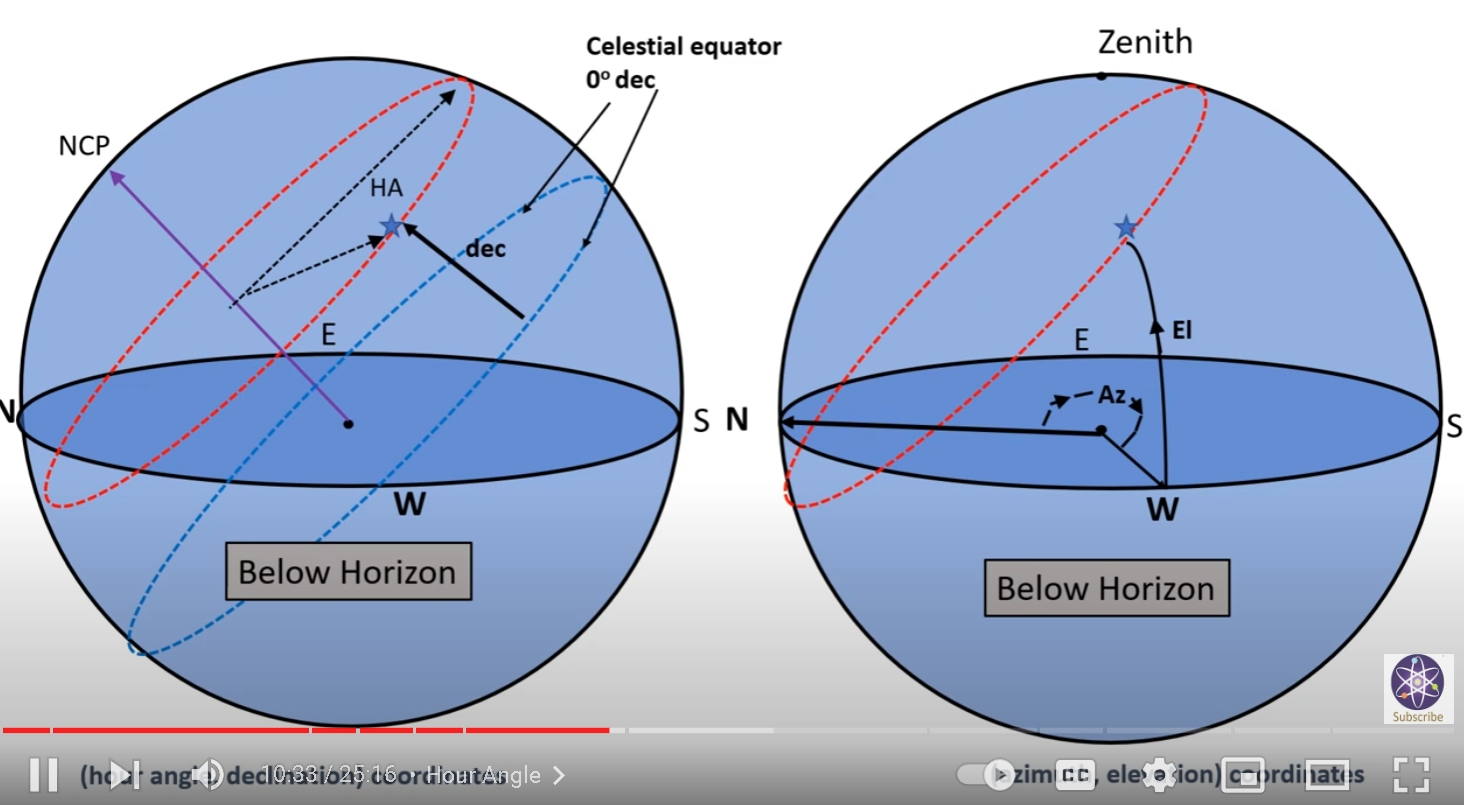

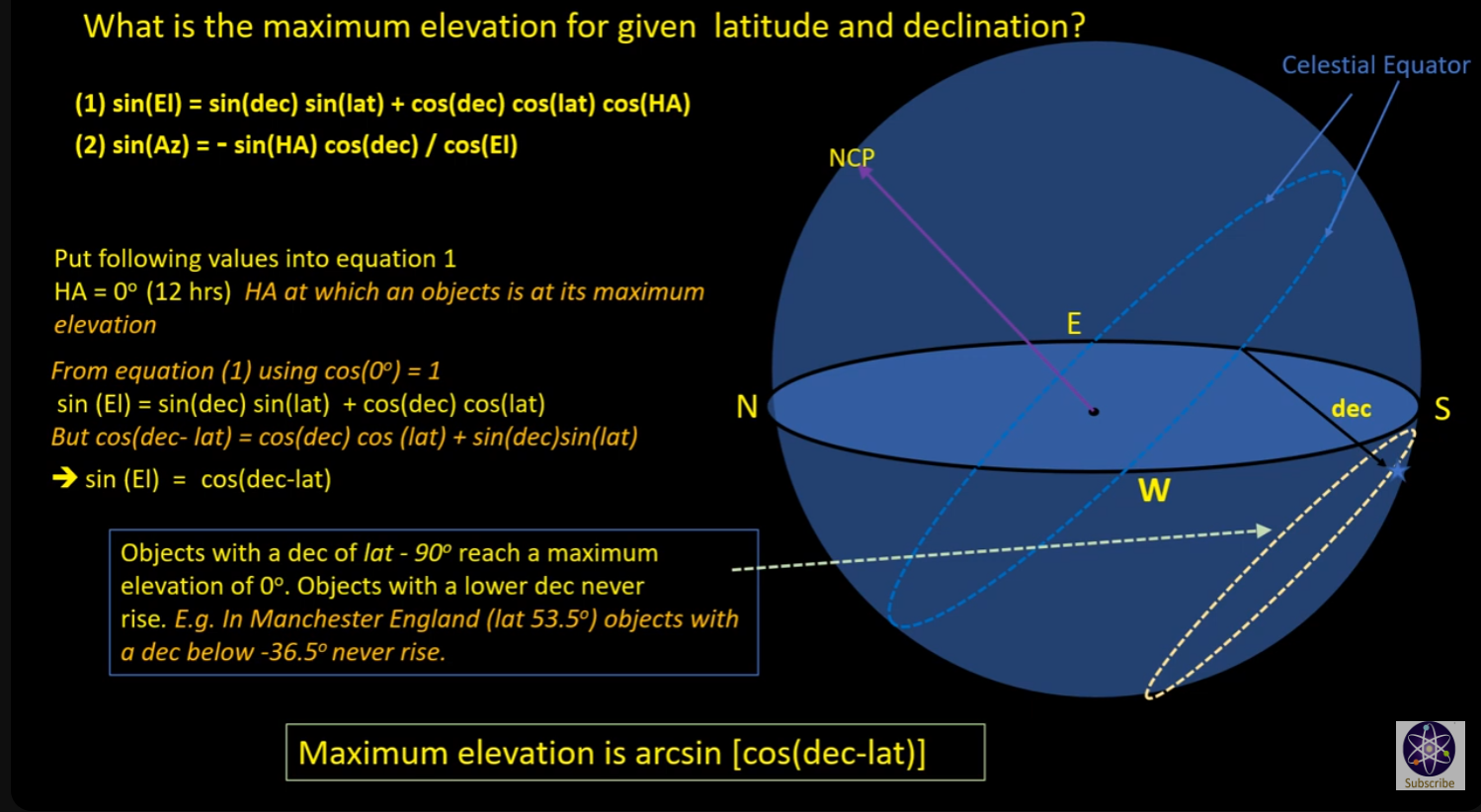

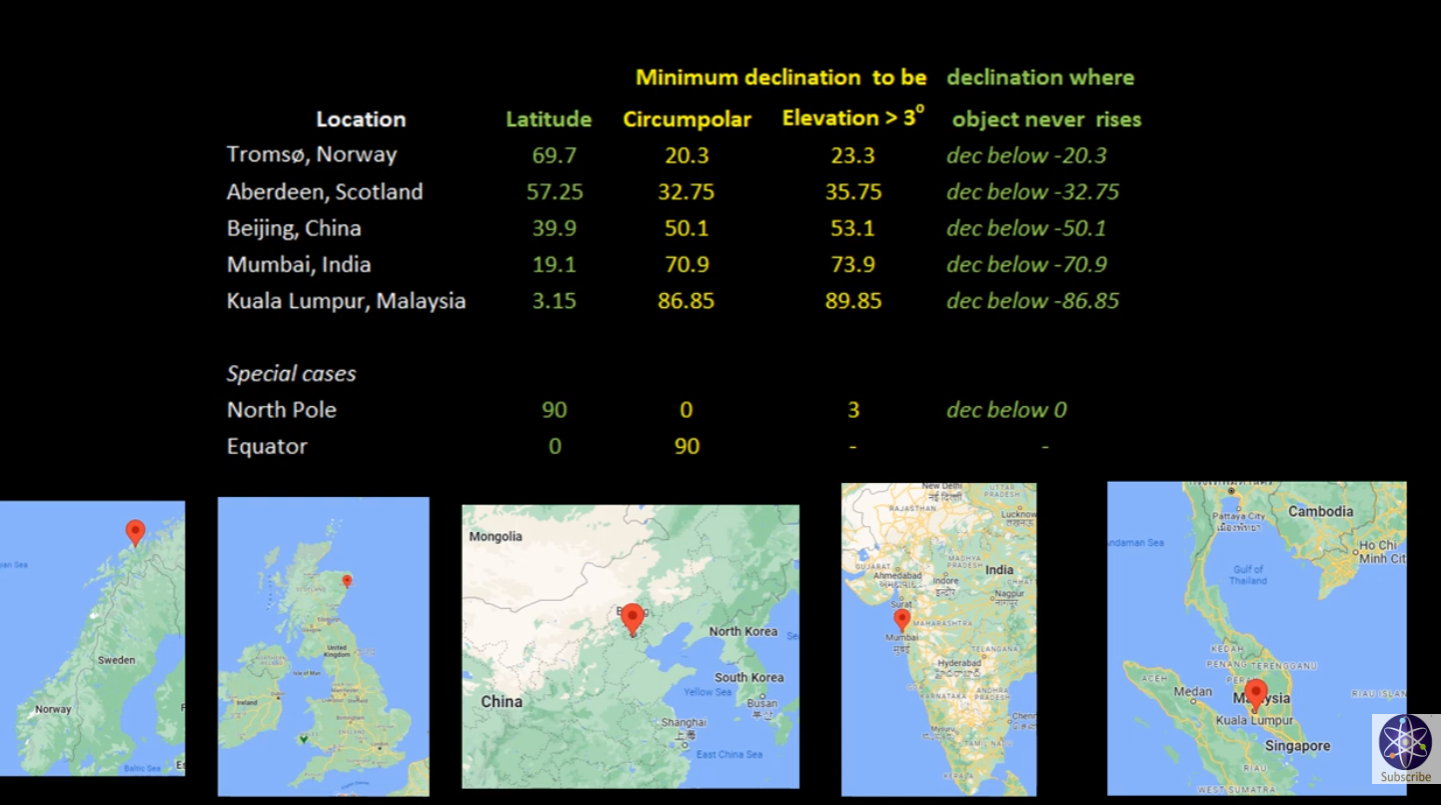

# Introduction to the Celestial Sphere & Astronomical Coordinates

The goal in the next chapter in the Almagest, Ptolemy’s goal is to is to find the angle between the celestial equator and ecliptic. These are both features on the celestial sphere which, whil…

---

The goal in the next chapter in the _Almagest_, Ptolemy’s goal is to is to find the angle between the celestial equator and ecliptic. These are both features on the celestial sphere which, while fundamental to astronomy, are not terms we’ve yet explored (aside from a brief mention in the first chapter of _Astronomia Nova_). So before continuing, we’ll explore the celestial sphere a bit. In addition, if we’re to start measuring angles on that sphere, we will need to understand the coordinate systems by which we do so.

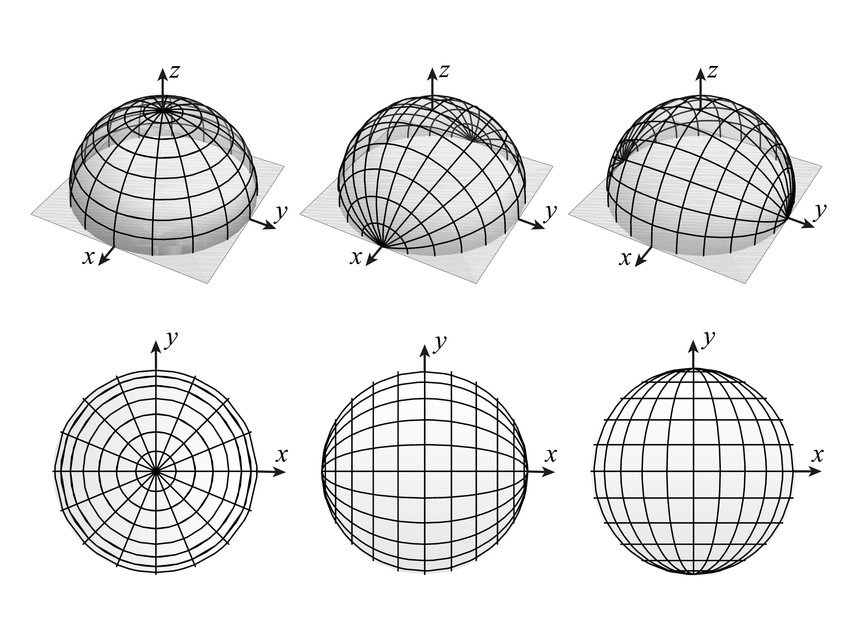

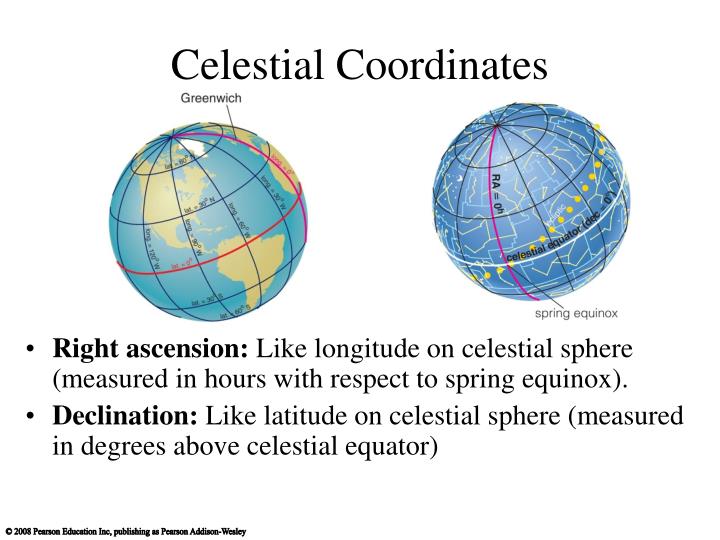

The first thing to understand is that the whole system is set up around spherical coordinates. In school, we deal so much in Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z) that thinking spherically (ϕ, θ) is challenging at first. But notice something about the variables I’ve just listed. In Cartesian, I’ve listed 3, but for spherical coordinates I’ve only listed 2.

In the Cartesian coordinates, the x, y, and z represent the left-right, back-forth, and up-down from a point of origin. In spherical, ϕ is the angle around, and θ is the up-down. To be complete, we could also include r, but since we cannot easily perceive distance to celestial objects, this is typically omitted for astronomical purposes.

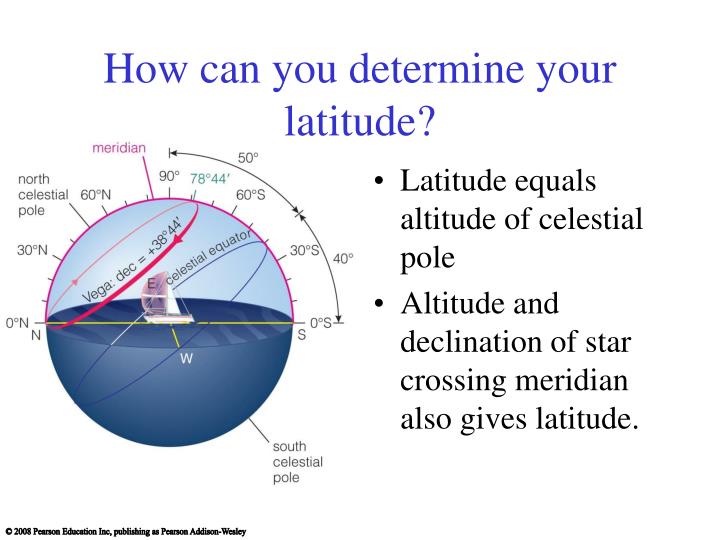

However, as with the Cartesian system, the spherical coordinates need a starting point, an origin. To begin, we take one locally. We use our horizon and the point directly north on that horizon. So if a star was located exactly on the horizon at north, it would be located at (0º,0º). The first of these numbers is the altitude (angle above the horizon). So if a star was located due north but was half way to the point straight up (the zenith), it would be (45º, 0º). While the coordinate system itself is set on the north point, we only allow that the altitude go up to 90º which indicates that we always take it from the closest point on the horizon instead of truly north.

The second coordinate is the _azimuth_. This is measured around the horizon starting at due north and going through east-south-west, in that order. So if a star was half way up the sky and due east, it would be at (45º, 90º).

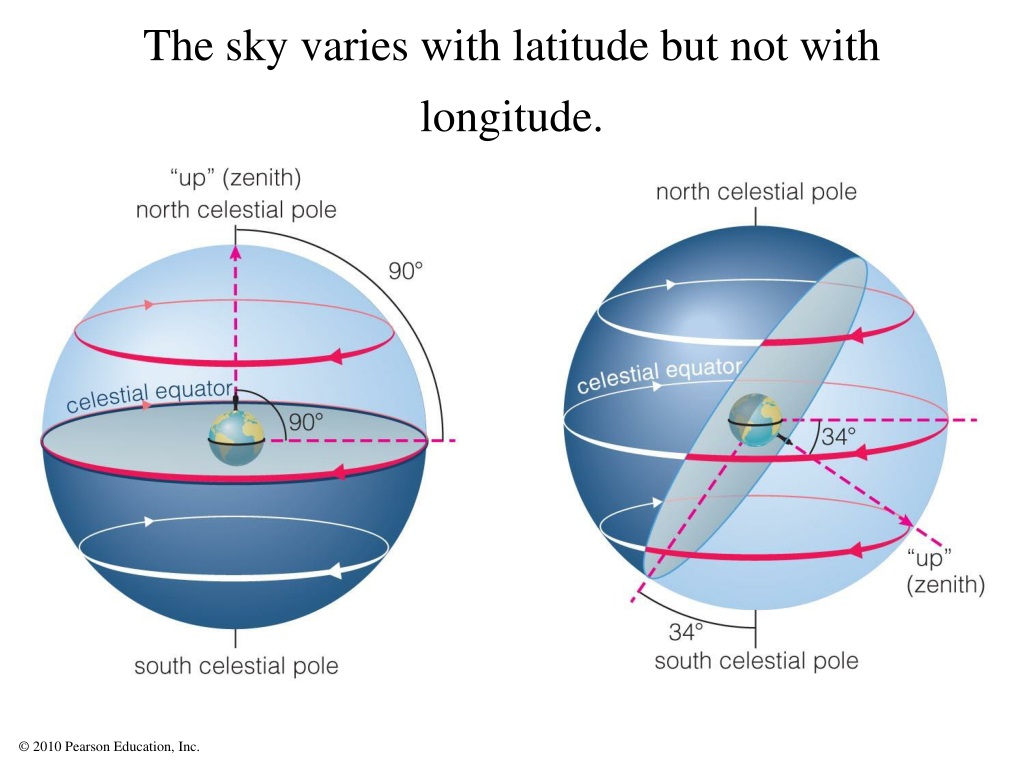

The problem with this system is that it is tied to our local point of view. To most astronomers in period, the Earth was fixed and the sky turned around it. In modern understanding it is the Earth that turns. But either way you look at it, the position of every object in the sky is changing from second to second.

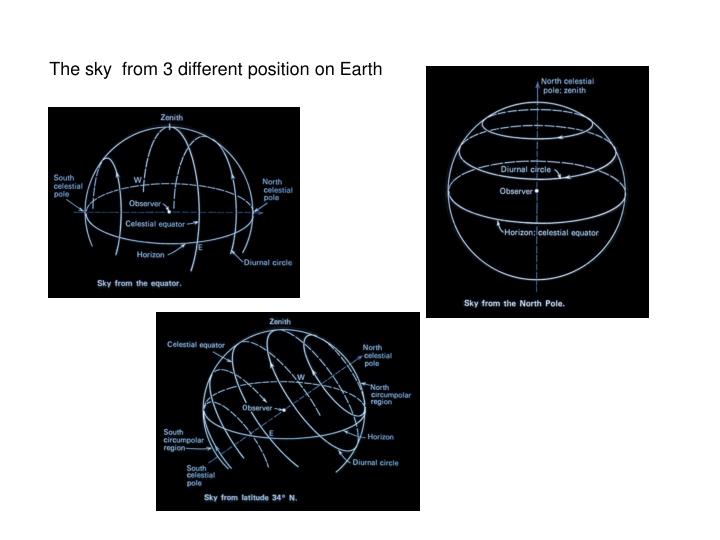

Worse, the Earth is spherical which means everyone will have a zenith pointing somewhere else. So you can’t even compare notes with friends. So for a truly useful system, we’ll need one that’s fixed to the sky. But as with all coordinate systems, we’ll need a point from which we can measure anything else. So before developing the new coordinate system, we’ll need to develop the celestial sphere itself.

First, we must understand that the dome of the sky we see above us is only half the picture. The other half of us is simply hidden beneath the ground. But two halves put together make it appear as if we’re at the center of a sphere. I could draw this, but being a two dimensional representation, it would simply look like a circle at this point. So to add a bit of reference, we’ll extend Earth’s equator out to that sphere. Not so cleverly, this is the celestial equator.

[](https://i0.wp.com/jonvoisey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/celestialsphere1.png?ssl=1)

This is a good start because, much like our horizon, it provides a plane from which we could measure an object’s position above or below. However, we still need a point on the celestial equator to serve as our origin for the around.

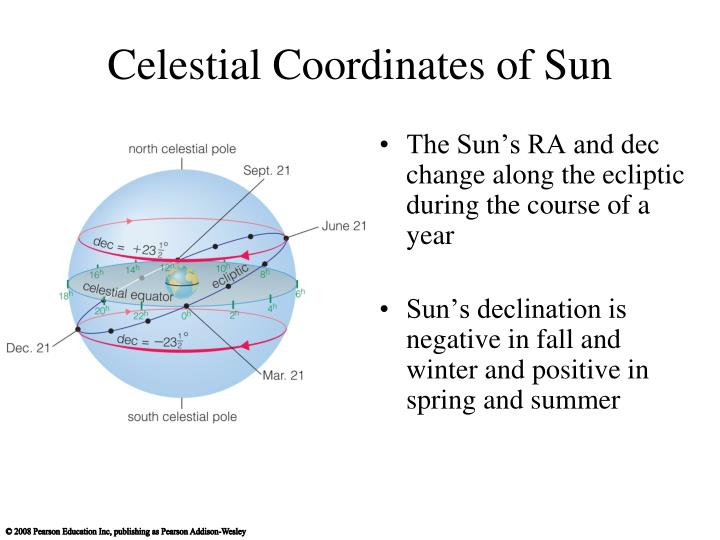

For this, astronomers used the position of the sun. If the path of the sun is marked out on the celestial sphere throughout the year, it traces a path known as the ecliptic.

[](https://i0.wp.com/jonvoisey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/celestialsphere2.png?ssl=1)

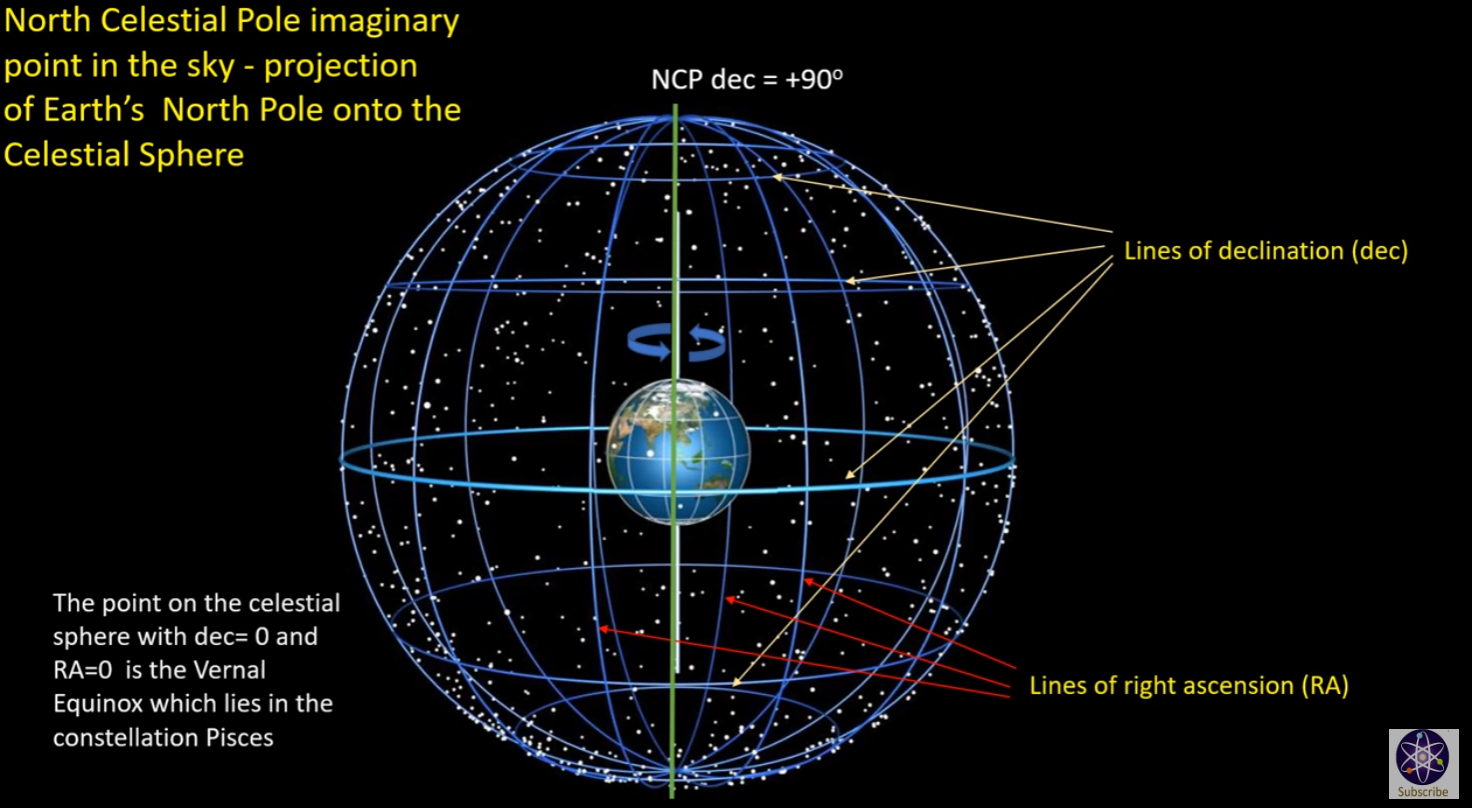

Note that the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator at two points. These are the equinoxes (vernal and autumnal). When the sun is at its highest point on the ecliptic, that’s the summer solstice and conversely, the low point is the winter solstice. For this coordinate system, the vernal equinox was the point chosen for the origin. Since (at the time[1](https://jonvoisey.net/blog/2018/06/introduction-to-the-celestial-sphere-astronomical-coordinates/#easy-footnote-bottom-1-367 "The vernal equinox not occurs in Pisces due to the Earth wobbling. As such all the astrological “zodiac signs” are off by nearly a month. Just another reason astrology is nonsense.")) the sun was then in the constellation of Aries the sign for the vernal equinox is often the symbol for Aries.

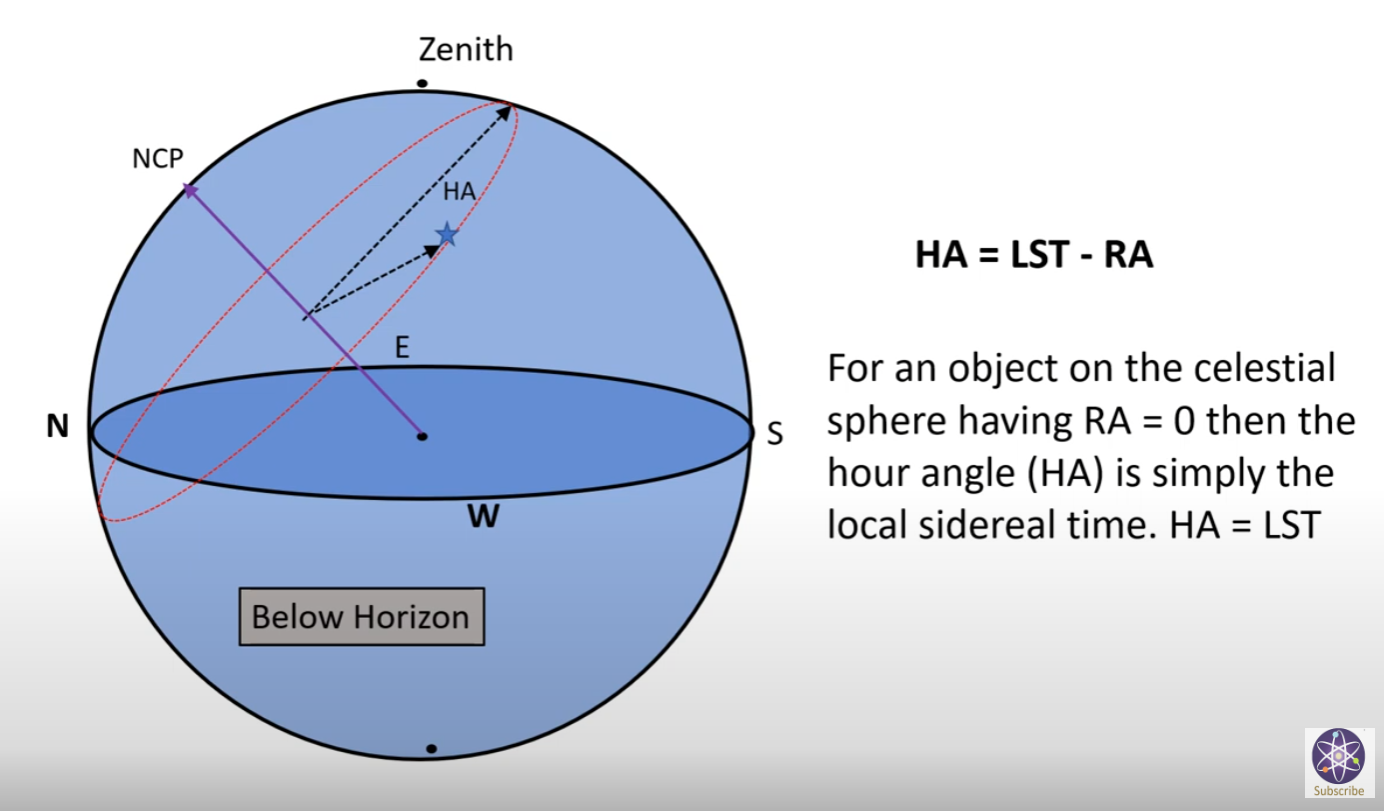

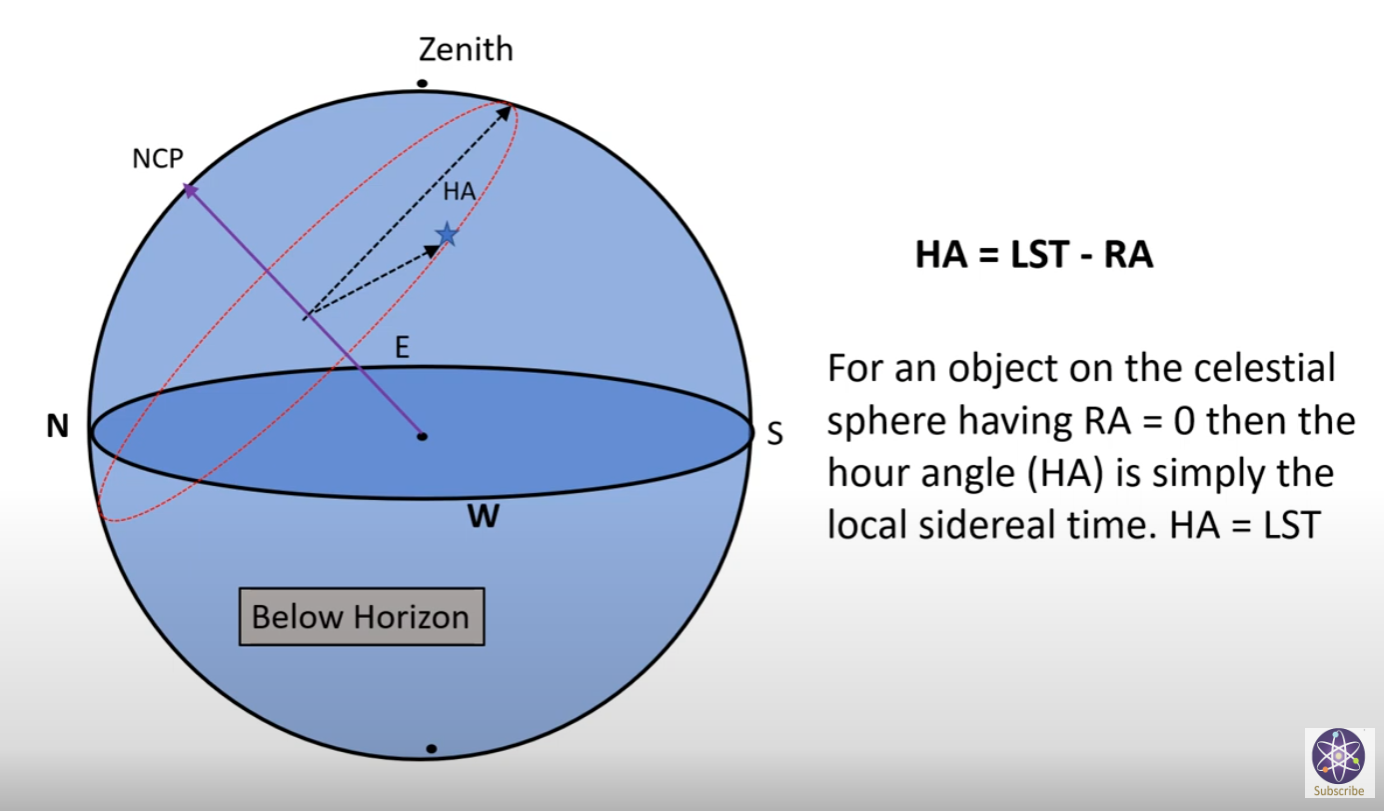

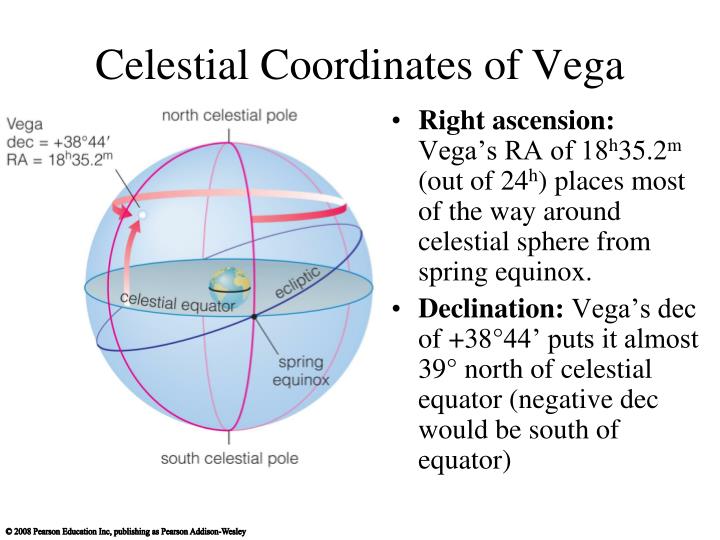

This system is known as the RA-Dec system which is short for Right Ascension and declination. RA takes the place of our azimuth. It’s measured around the celestial equator starting from the point of the vernal equinox, towards the summer solstice, autumnal equinox, and winter solstice in that order. However, instead of measuring this in terms of degrees, astronomers to this day measure it in hours, minutes, and seconds – a throwback to the sexagesimal system.

Meanwhile, the declination is measured just like the altitude: up from the ecliptic in degrees with 90º being the maximum.

Let’s take a quick example:

[](https://i0.wp.com/jonvoisey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/celestialsphere3.png?ssl=1)

Here I’ve sketched in a star. Starting from the vernal equinox, it’s closest point on the celestial equator is a little past the summer solstice but not yet to the autumnal equinox. So since the equinoxes and solstices are every 14 of the 24 hours, the summer solstice would be at 6 hours. Thus, the star is somewhere around 7-8 hours RA. Let’s call it 7.5 hours which is 7 hours, 30 minutes, abbreviated 7h30m.

From there, it’s 23 way between the celestial equator and the 90º point I’ve sketched in. Let’s call it 65º. But it’s also _above_ the equator. That gets noted by the fact that the declination is positive. Objects below the ecliptic have a negative declination.

So it’s RA-dec position would be 7h30m, 65º.

Another thing to note in the diagram above is that I’ve drawn it with north being at the top and south at the bottom. This places the vernal equinox on the far side in this sketch because, when viewed top down, the Sun seems to move around the celestial sphere counter clockwise. We’ll be seeing this behavior a lot more as we start getting into the various models of Ptolemy, Copernicus, and Brahe, so I wanted to get everyone used to it early.

While it doesn’t directly pertain to the celestial sphere, this is also a good time to look at some topics related to the spherical geometry since we’re very shortly going to need to be going through some math in this coordinate system.

The first is the idea of great circles and small circles. A great circle is a circle whose center goes through the center of the sphere. So the ecliptic and celestial equator or both great circles. But consider the apparent path of the star:

[](https://i0.wp.com/jonvoisey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/celestialsphere4.png?ssl=1)

Its nightly path does _not_ pass through the center of the sphere. Thus, it is known as a small circle.

I’ll also remind the reader that the sun’s apparent path from day to day is also not a great circle; the ecliptic is the path the sun takes with respect to the background stars over the course of the entire year. On the day-to-day, the Sun does not etch a great circle either. This is an important distinction.

So why are great circles important? Although I didn’t explicitly call it out previously, we’ve already been using them in a sense. When we connected the star to its closest point on the celestial equator, that path was actually part of a great circle. It turns out that the shortest distance between any two points on a sphere is to take the great circle that intersects them both[2](https://jonvoisey.net/blog/2018/06/introduction-to-the-celestial-sphere-astronomical-coordinates/#easy-footnote-bottom-2-367 "This is why if you view an airplane’s path over long distances on a normal, flattened map (known as a Mercator map), they often take what appear to be long arcs instead of straight lines – it <em>is</em> a straight line, but when distorted to be on a flat surface, it appears to be an arc."). Thus, when I looked at the [angular separation between between the Sun and Mars in _Astronomia Nova_, Ch 1](https://jonvoisey.net/blog/index.php/2018/05/11/astronomia-nova-chapter-1/#more-17), that distance was in part defined by the great circle distance between the two.

Another reason to care about great circles is that the intersection of three great circles defines a spherical triangle, shown below in red.

[](https://i0.wp.com/jonvoisey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/celestialsphere5.png?ssl=1)

Something to note about spherical triangles is that they don’t particularly behave like planar triangles. Their angles don’t add up to 180º. Trig functions don’t work on them directly. So when dealing with this topic in modern astronomy, a large chunk of learning to work in spherical coordinates also involves relearning how geometry and trigonometry work on spheres which includes building new tools. That would then allow for things like the conversion between the alt-az system and the RA-dec system.

However, as we noted previously, Ptolemy didn’t have trigonometric functions available to him. So we’ll have to see exactly how he approaches this issue…

1. The vernal equinox not occurs in Pisces due to the Earth wobbling. As such all the astrological “zodiac signs” are off by nearly a month. Just another reason astrology is nonsense.[](https://jonvoisey.net/blog/2018/06/introduction-to-the-celestial-sphere-astronomical-coordinates/#easy-footnote-1-367)

2. This is why if you view an airplane’s path over long distances on a normal, flattened map (known as a Mercator map), they often take what appear to be long arcs instead of straight lines – it _is_ a straight line, but when distorted to be on a flat surface, it appears to be an arc.[](https://jonvoisey.net/blog/2018/06/introduction-to-the-celestial-sphere-astronomical-coordinates/#easy-footnote-2-367)

[https://x.com/AntiDisinfo86/status/1761660552110014579?s=20](https://x.com/AntiDisinfo86/status/1761660552110014579?s=20)

[https://stemonline.tech/en/earth-science/celestial-sphere/](https://stemonline.tech/en/earth-science/celestial-sphere/)

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nB79vXGZj8](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nB79vXGZj8)

---

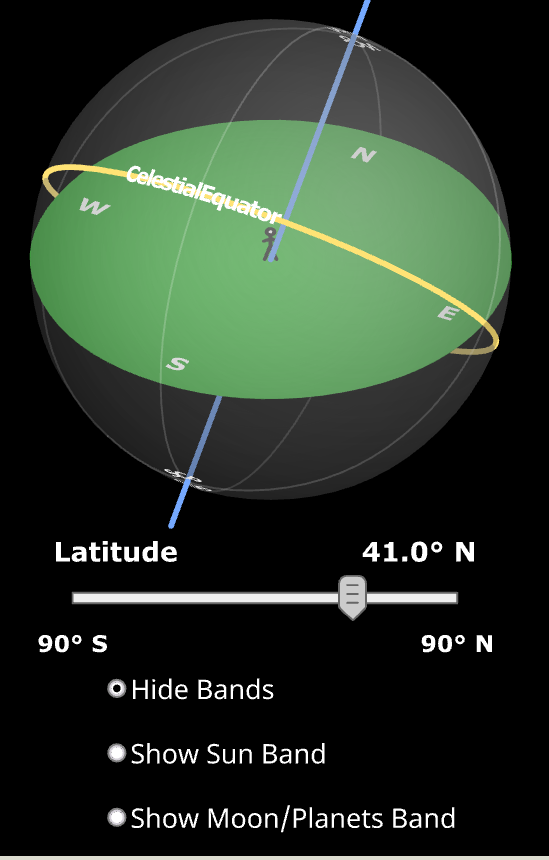

## Description

The NAAP Rotating Sky Lab introduces the horizon coordinate system and the “apparent” rotation of the sky. The relationship between the horizon and celestial equatorial coordinate systems is explicitly explored.

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7v1mGsQNdQ](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7v1mGsQNdQ)

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S21dGzLS5wA](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S21dGzLS5wA)

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nB79vXGZj8](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nB79vXGZj8)

[https://astro.unl.edu/naap/motion2/starpaths.html](https://astro.unl.edu/naap/motion2/starpaths.html)

hs of the Stars

[https://astro.unl.edu/naap/motion2/motion2.html](https://astro.unl.edu/naap/motion2/motion2.html)

Stars move across the sky.

Credit: Chris Christner

## Rotation of the Sky

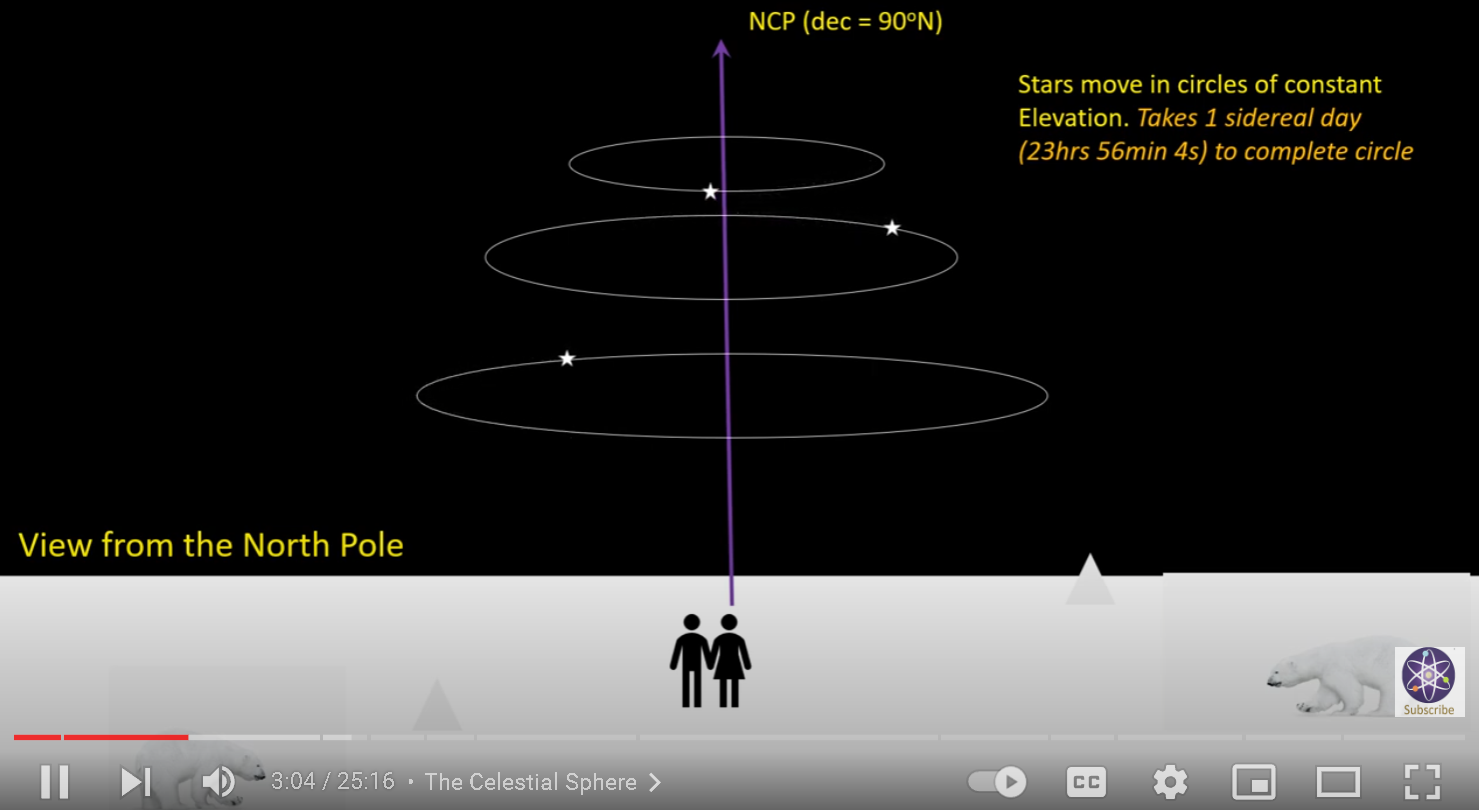

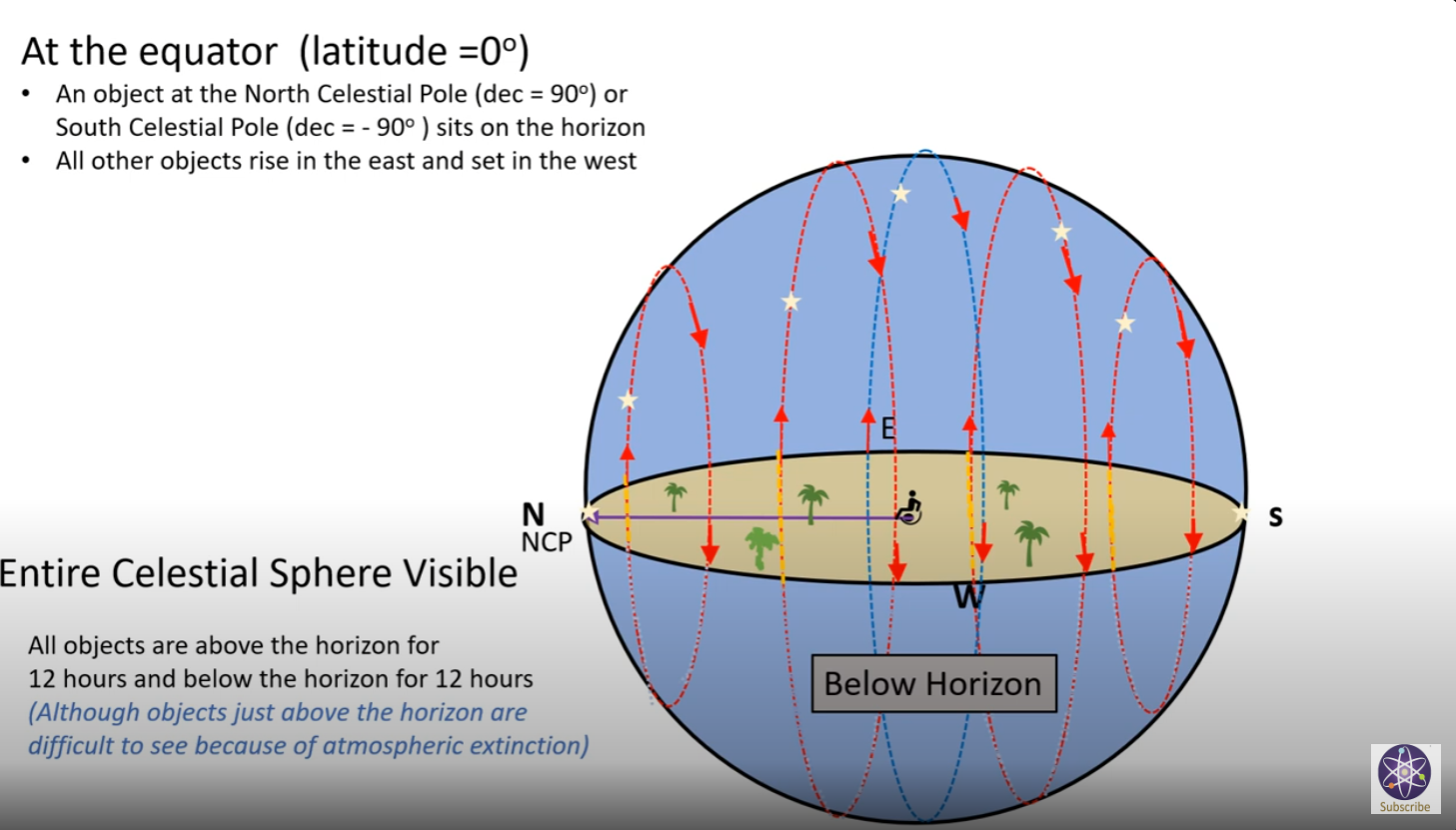

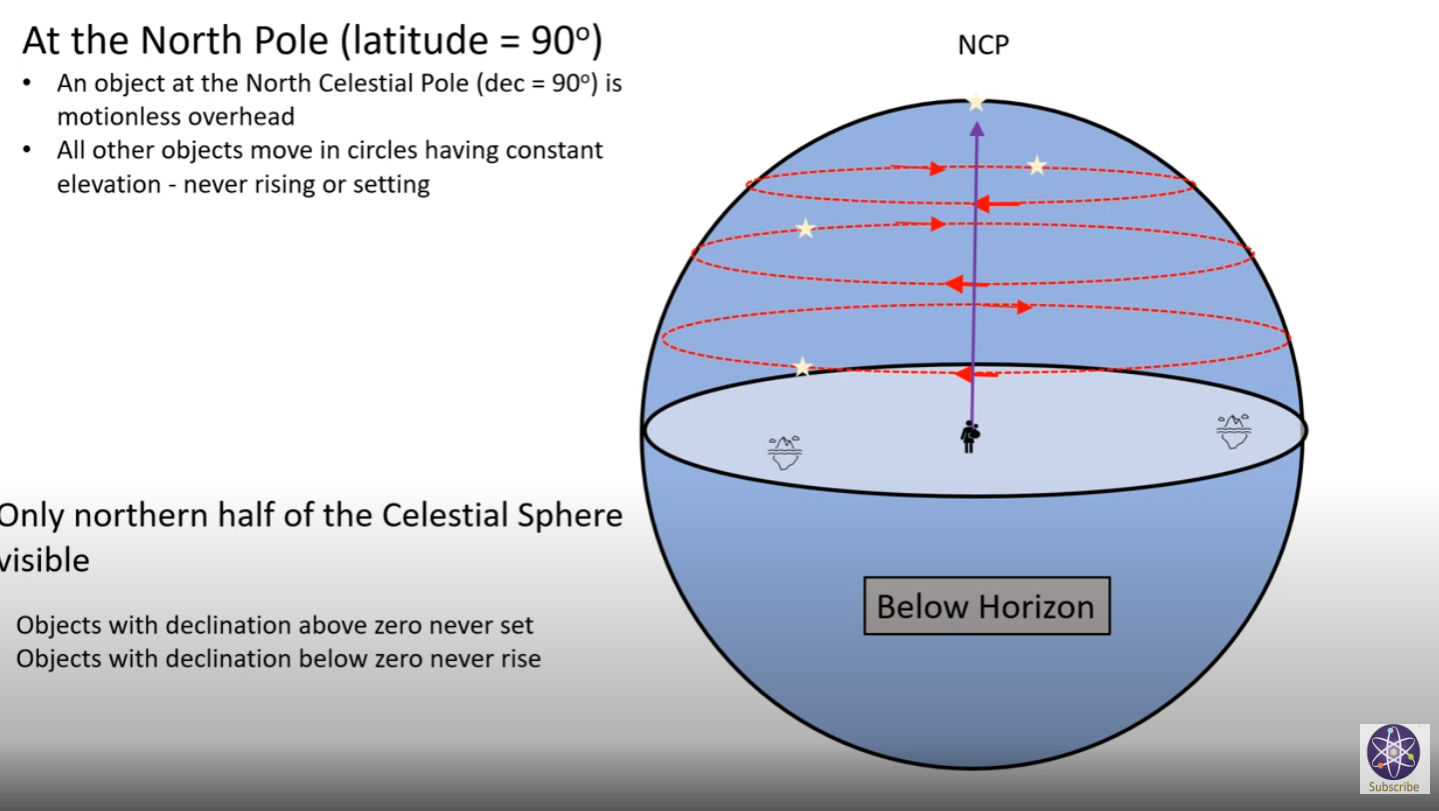

Because the earth is rotating the sky appears to rotate. Viewed from above the north pole, the earth is rotating counter-clockwise. For an observer on the earth, objects move from east to west (this is true for both northern and southern hemispheres). More accurately put, when looking north, objects in the sky move counter-clockwise.

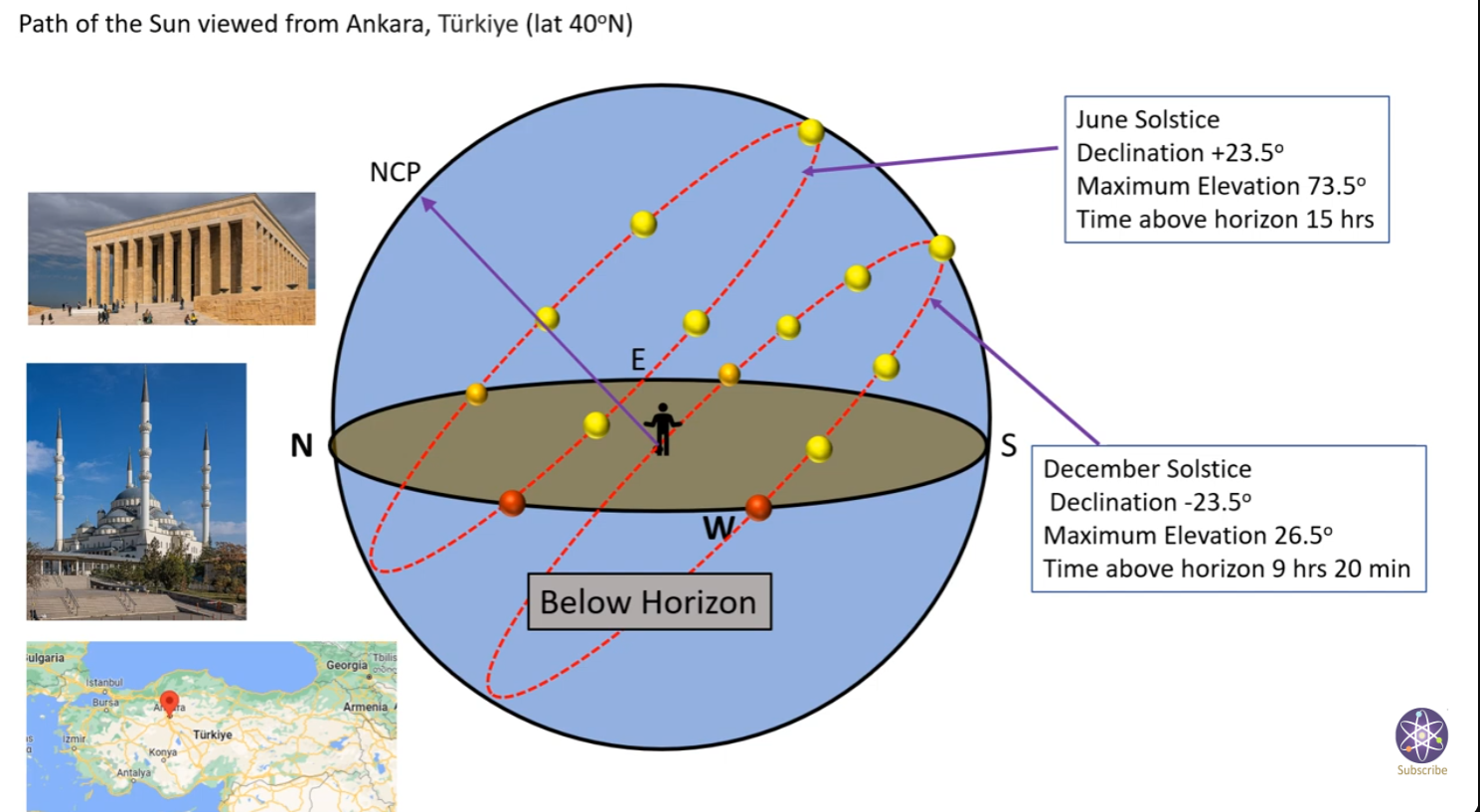

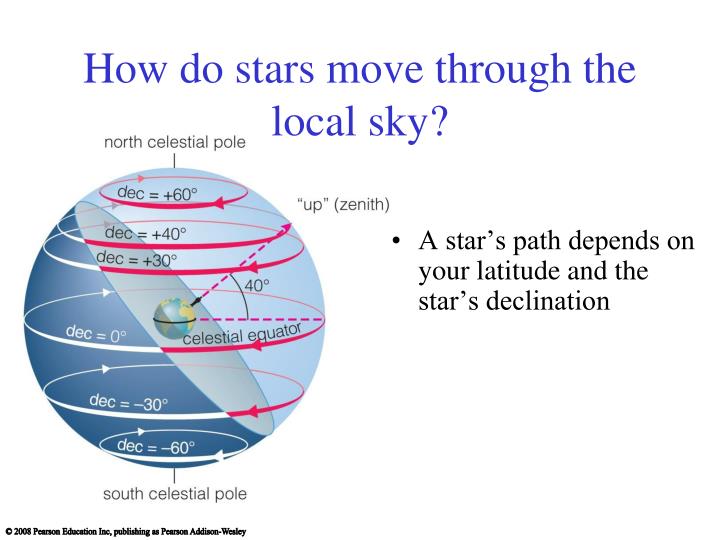

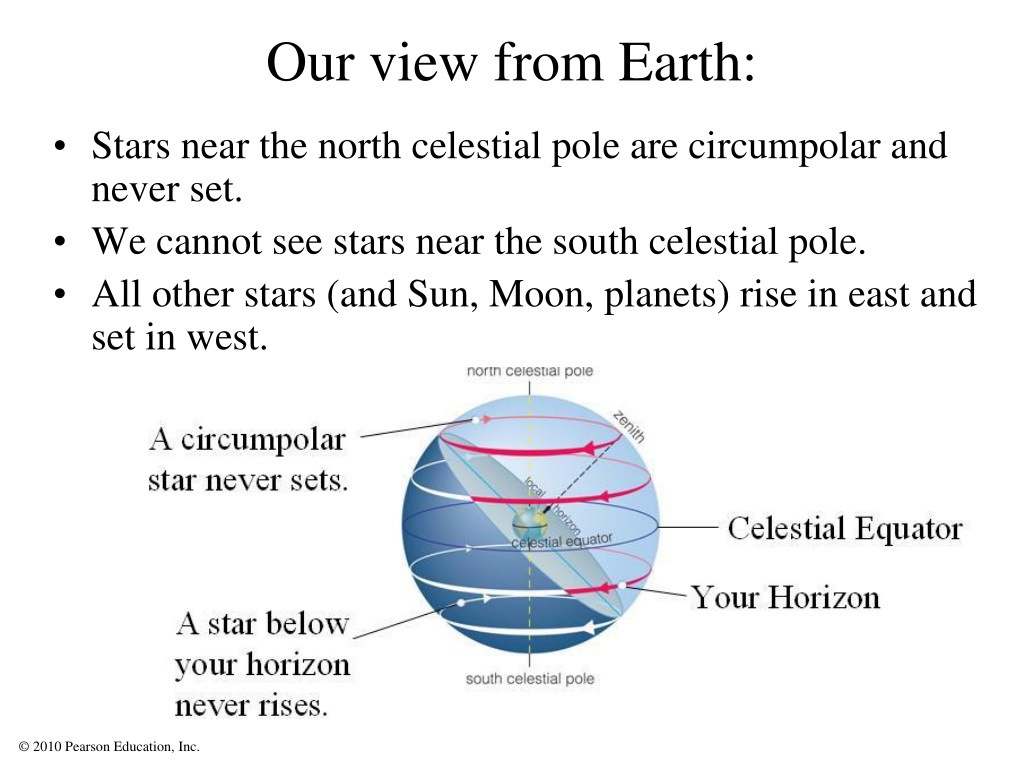

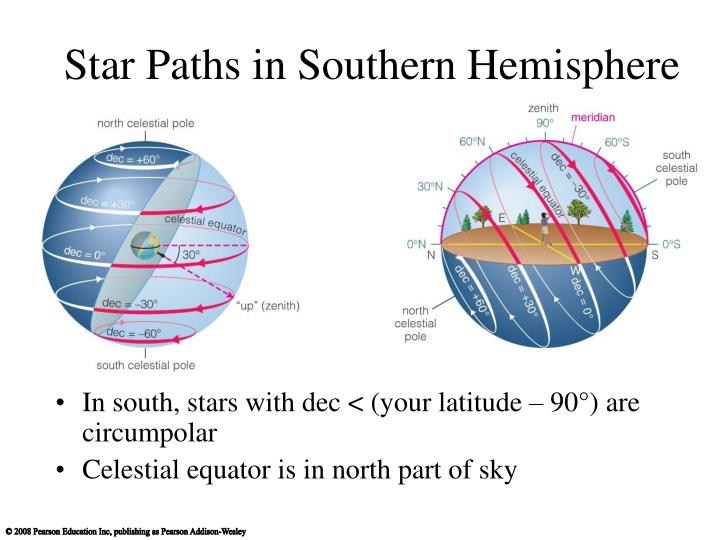

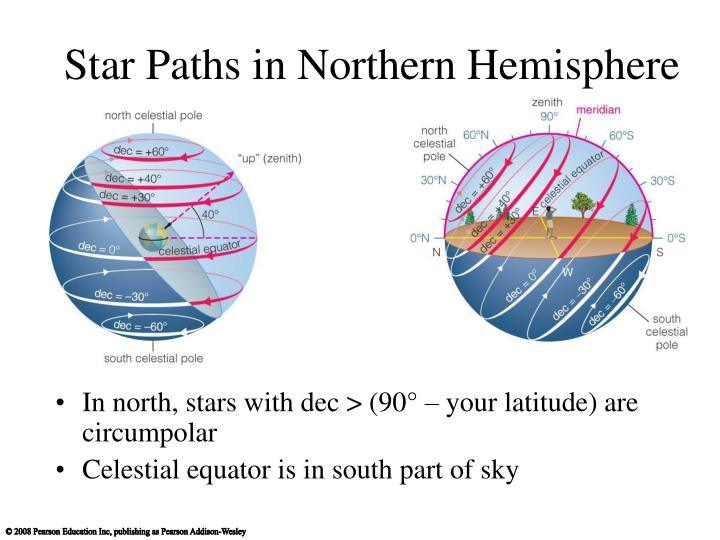

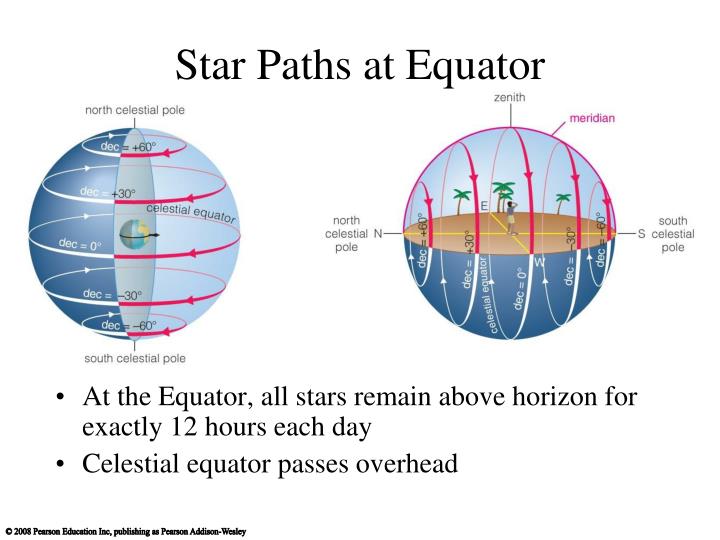

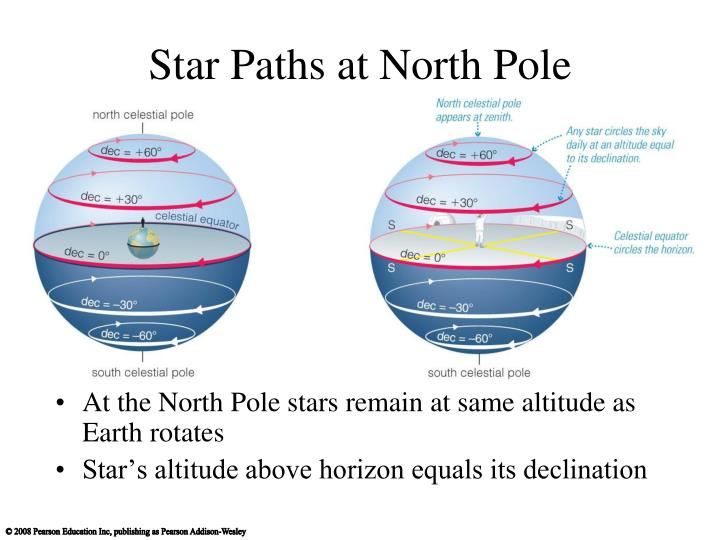

Though all objects rotate in the sky, the observed path stars make in the sky depend on the observer's latitude. Some are always in the observer's sky, some some of the time, and others are never observable. These different ways of classifying stars are discussed below.

Different kinds of star paths.

## Rise and Set Stars

During the rotation of the earth, some stars rise from below the eastern horizon and later set below the western horizon. Appropriately enough, these stars are called rise and set stars. They are indicated by the yellow star trails in the animation to the left.

The angle rise and set stars (including the sun) make with the horizon as they rise is the same for all rise and set stars for that observer. Specifically, the angle is 90° - |observer's latitude|. They make this same angle in west. In the northern hemisphere the angle is tilted towards the south and in the southern hemisphere the angle is tilted towards the north.

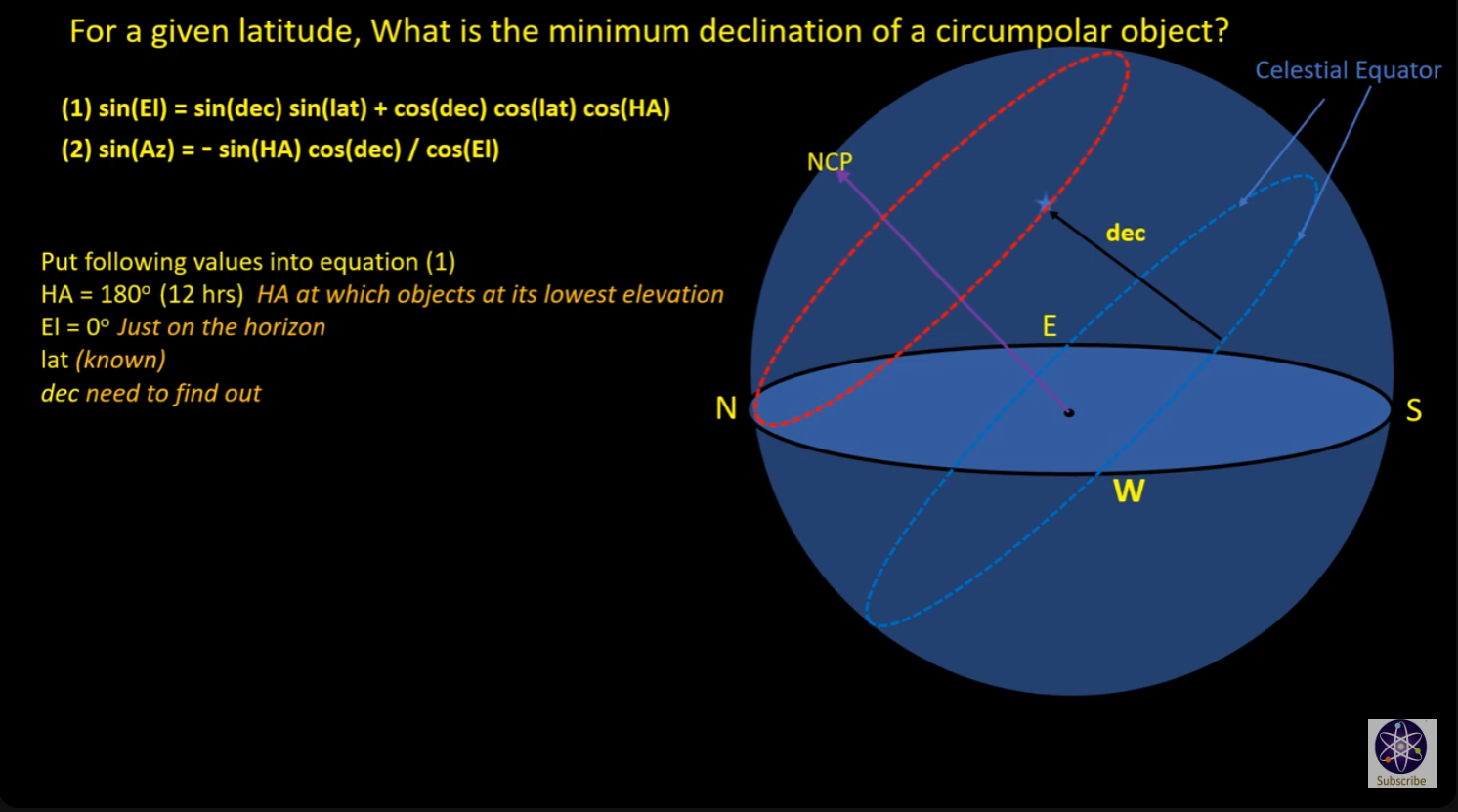

## Circumpolar & Never-Rise Stars

Stars near the celestial poles make small circles and may not pass the horizon plane. If they are always above the horizon they are called _circumpolar stars_. If they are always below the horizon they are _never rise stars_. Circumpolar stars for the northern hemisphere are never-rise stars for the southern hemisphere and vice versa. These stars are indicated by blue (northern hemisphere stars) and red (southern hemisphere stars) in the figure to the left.

[https://astro.unl.edu/naap/motion2/skybands.html](https://astro.unl.edu/naap/motion2/skybands.html)

# Bands in the Sky

---

Locations of objects in the sky.

## Object Location in the Sky

The celestial poles and the celestial equator can be used as reference points for identifying the locations of other objects of interest in the sky – like the sun, moon, and visible planets. It is often instructive to crudely describe where these objects can be located in the sky for various latitudes on the earth with “bands” of declination.

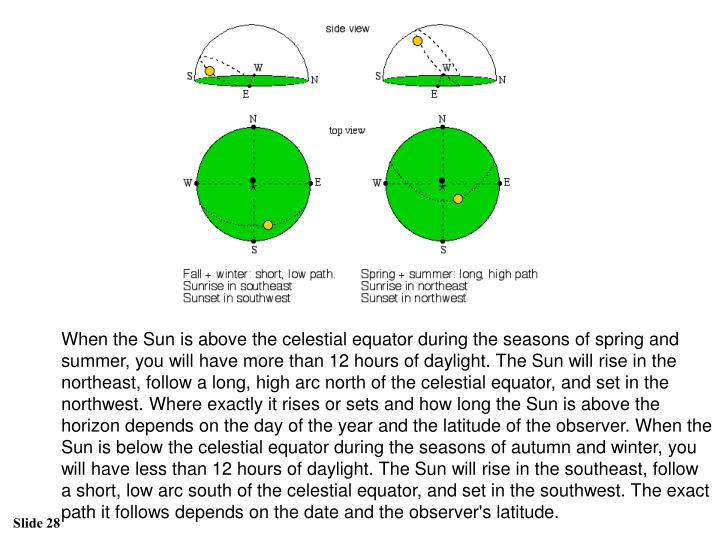

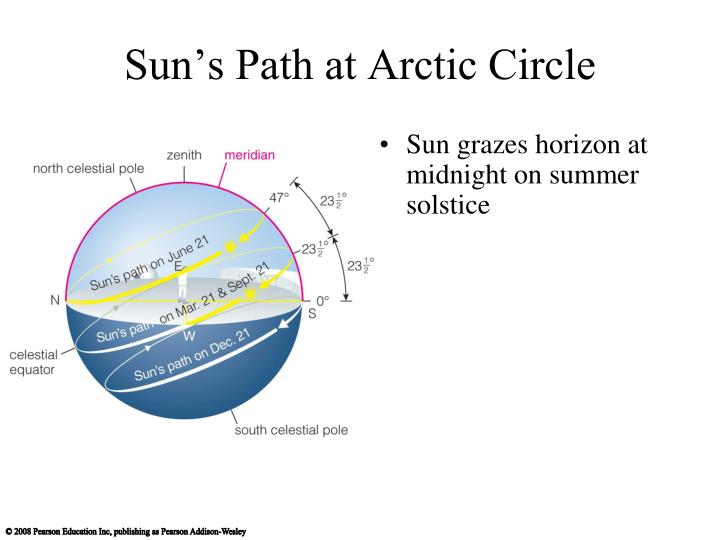

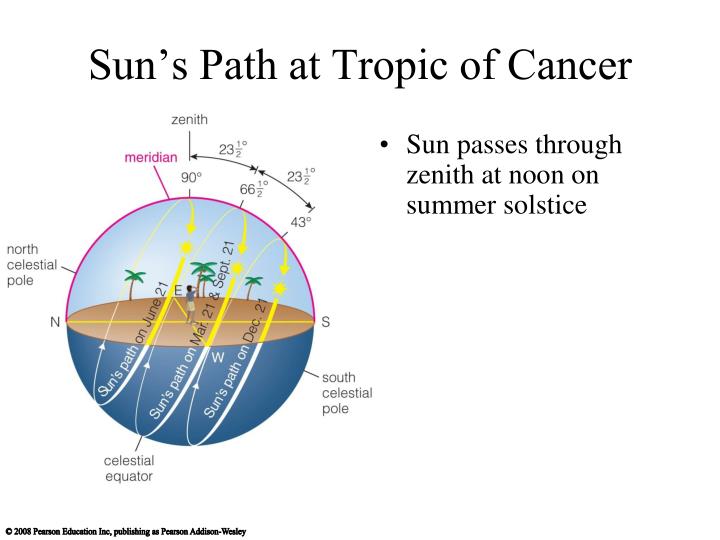

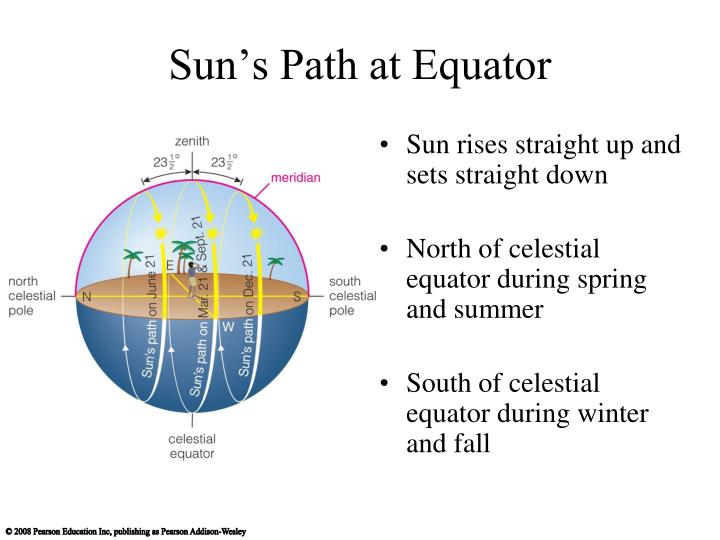

The ecliptic is the plane of the earth's orbit about the sun. Because the earth is tilted (its obliquity) about 23.5° to this orbital plane, the sun's declination is always between +23.5° on the summer soltice and -23.5° on the winter solstice. Thus one can picture a band 47° wide centered on the celestial equator. The sun is always in this band.

The orbits of other objects in the solar system are described with relation to the ecliptic. The moon's orbit is inclined by about 5° to the earth-sun orbital plane. Thus the moon is located in a larger region of the sky.

The orbital inclinations of the brighter planets are small, for example Mars' orbital inclination is about 2°. Because orbital inclination is measured from the center of the sun and declination is measured from the center of the earth, Mars can be as much as 6° off of the ecliptic. The only planet that can be very far from the ecliptic is Pluto but it can't be observed without a good-sized telescope. Thus, the location bands for the bright planets is very similar to that of the moon and the two are shown as one 60° band in the Skyband Simulator.

Links to this page

[69 Miles Per Degree](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/69+Miles+Per+Degree)

[Coordinate Systems](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Coordinate+Systems)

[G Projector Map Software](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/G+Projector+Map+Software)

[Geodesic Surveying, Spherical Excess](https://publish.obsidian.md/shanesql/Geodesic+Surveying%2C+Spherical+Excess)